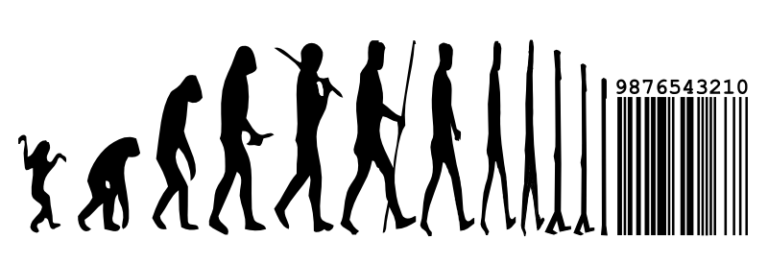

Subculture has become a billion dollar industry.

Clark 2003

Are subcultures dead? In today’s world, the very idea of a subculture has become mainstream (Clark 2003). The increasing commodification of all aspects of society poses a risk to subcultures becoming commodified beyond the point of recognition, decimating any sense of authenticity (Clark 2003; Connor and Katz 2020). It is questionable if subcultures are able to continue to thrive under these conditions, or if they have been “killed” by commodification. However, the future of subcultures may be influenced by commodification in a multitude of ways. Although processes of commodification are certainly able to change subcultures and move their focuses from the often resistance-based origins to the purchase and exchange of products, subcultures can exist in opposition to this process with their own methods to resist it (Clark 2003; Moore 2005).

Commodification is the process of turning aspects of a subculture, or a subculture itself, into a product to be sold. The first step of this process is appropriation, during which corporations extract ideas from “underground” cultures, usually without permission from participants. This idea of cultural appropriation differs from the more commonly known definition that emphasizes how dominant cultures inappropriately borrow significant symbols from minority cultures for aesthetic purposes.

Seeing the profitability of subcultures, corporations can successfully market them to mainstream audiences and make a profit (Moore 2005). As a subculture is increasingly commodified, it may lose meaning and authenticity to its original participants. For instance, the commodification of Goth subculture by companies like Hot Topic and the marketing of Goth events to tourists have turned Goth into a mainstream label (Gaea 2015; Hanks 2011; Spracklen and Spracklen 2014).

Goth has been used as a catch-all label for young people who like heavy metal, or emo, or punk, a way of defining anyone who dresses in black as an unwanted Other... Goth has transcended a musical style to become a part of everyday leisure and popular culture.

Spracklen and Spracklen 2014

Theories of commodification discuss how subcultures and their symbols become profitable. Because objects act as communication that represents deeper meanings, purchased objects can easily become subculturally significant (Hebdige 1981: 95). Some views on subcultures suggest that subcultures function as just another thing to shop for, as a facet of one’s identity that they can purchase ready-made with little effort, self-reflection, or personal meaning beyond the aesthetic. For instance, postmodern theory posits that in a consumerist culture, subcultures are just “another set of images” for consumption (Haenfler 2023:43). In this case, subcultures are void of any meaning outside of consumerism. Similarly, critical theorists argue that the general population is fooled by the ruling class into accepting the status quo, partially through the consumption of popular culture. Pop culture is part of how the ruling class disseminates their dominant ideology, pacifying people and preventing the development of class consciousness. Thus, participants in subculture are just passive consumers.

Disney, one of the largest entertainment industries in the world, owns multiple media companies and dominates the sphere of

entertainment. Audiences rush to see the latest Disney movie, led on by the brand name.

The culture industry, an idea developed by Horkheimer and Adorno, describes the production of culture on an industrial scale that aids capitalist goals (Buchanan 2018). The role of the culture industry in spreading consumerism and attempting to allow consumers to feel unique and like their life is different from the mainstream while still conforming to popular interests allows deviant ideas and images to change into something mainstream that can make money. This conformity to popular ideas with the promise of being different can result in the production of more formulaic goods that relate exclusively to considerations of commonly-liked material over original ideas or concepts that pose a legitimate challenge to the mainstream. Marvel movies are a prime example of how an entertainment company produces formulaic media on a mass scale that serves as anti-revolutionary propaganda.

In a more optimistic view, we can see subcultures as a response to consumerist conditions and as efforts of resistance against commodification. Clark (2003) argues that subcultures like punk have invented new ways of being subcultural in an era of consumerism. While corporations have commodified the aesthetics of punk, its authenticity persists through political action. In addition, the idea of participatory culture emphasizes the agency that subculture participants have in appropriating and changing culture as active contributors. For example, fandoms encourage people to creatively contribute to media by making fanart or writing fanfiction, making their own meaning from so-called “pacifying” or “worthless” media.

The impacts of commodification include syncretism, diffusion, and defusion. Syncretism is the process of subcultures overlapping, sharing ideas, and becoming increasingly similar to one another. With the commodification of subcultures like Goth, punk, and scene, the styles and symbols of these subcultures have blended together under one alternative umbrella. Chain stores like Hot Topic that capitalize on alternative styles further perpetuate the intermingling of these subcultures.

Diffusion occurs when subcultural ideas, styles, values, and norms spread to a wider audience. One example of this process is the popularization of tattoos (Kosut 2006). While tattoos used to be symbols of deviance, criminals, and the lower-class, they have been repackaged as cool, desirable, and artistic. Media and celebrities played a significant role in spreading tattoos to the mainstream, so now people from all walks of life sport tattoos. However, tattoos are a unique example of commodification in that they do not function like a typical commodity. Since tattoos are permanent on the body, they resist “throw-away” consumer culture (Kosut 2006).

Finally, defusion is the process of depoliticizing or watering down the values, meanings, and subversive potential of a subculture. Electronic dance music (EDM) is an example of how a subculture that was originally characterized by “anti-consumerism” and “resistance to authority” turned into a “billion-dollar industry” (Connor and Katz 2020). These deviant characteristics were used to market ticketed events with celebrity DJs, transforming the EDM scene into a commodity.

Thus, the politically dissident strategies of resistance, that characterized the early EDM subculture, became their undoing as the liberating aspects of these tools became reconfigured for use by agents of mass marketing.

Kosut 2006

Commodification of subcultures and subcultural symbols is not new, and deviance has continuously been used for marketing, such as with Harley-Davidson motorcycles, which promotes a deviant image of bikers while generating profit for the company’s businesspeople (Schouten & McAlexander 1995). Although perhaps nostalgia may result in views of scenes as previously noncommercial and free from capitalistic influence, many subcultures had profitable aspects from their origins.

Many subcultures that encourage specific fashion have historically fed back into the fashion industry, such as punks and mods, who both purchased clothes and influenced later fashion trends (Hebdige 1981: 95). The history of subcultural transaction occurs from the early days of punk. Even at the start of punk, outsiders perceived the subculture as a moneymaking scheme, which contained some truth, as punk was integrated into the mainstream. Vivienne Westwood and the Sex Pistols exemplified the focus within some parts of punk on commercial viability (Liptrot 2014).

Some subcultures where commodification has occurred include music-based subcultures such as punk, EDM, and alternative music. Subcultures with a strong focus on appearance, fashion, or aesthetics are particularly vulnerable, such as hipsters and goths. Subcultures focused on nominally DIY activities such as van life, steampunk, and disaster prepping subcultures may also have ways to make these activities easier marketed back to them through the promise of quicker and lower-effort attainment of a subcultural ideal. Taken to the extreme, this may result in financial ability to attain subcultural products becoming the standard for participation in a subculture and leaving behind the subculture’s original nature. Furthermore, the commodification of subcultures has effects on their perceived authenticity (Spracklen and Spracklen 2014). Long-time participants of a subculture may express disdain for the mainstreaming of the subculture, believing that it loses meaning when absorbed into consumer culture, but may also underestimate the degree to which subcultures have always been commodified due to nostalgia.

Additionally, commodification is not simply something imposed on a subculture through outside forces, but is something that members of the subculture actively participate in for their own benefit, for better or for worse:

I remember, basically the aesthetics and the music were completely co-opted into modern consumptive culture. And they were co-opted by us, those of us who went and got jobs in the design field. Fuck you guys! Right? I mean I don’t blame them, but it happened, and it happened fast and it was complete. And I don’t know, now that the Internet’s here and now that that layer of design geeks took the good stuff and ran, I don’t know if something similar is going to emerge in such a way where it takes eight years for it to move to mainstream culture. I think the turnover now is going to be so fast that it’s not going to be as possible to have that kind of subculture.

-Helen, 33 y/o punk, from Debies-Carl, 2015

Although subcultures will certainly continue to change through commodification, this may have more effects than simply “killing” subcultures.

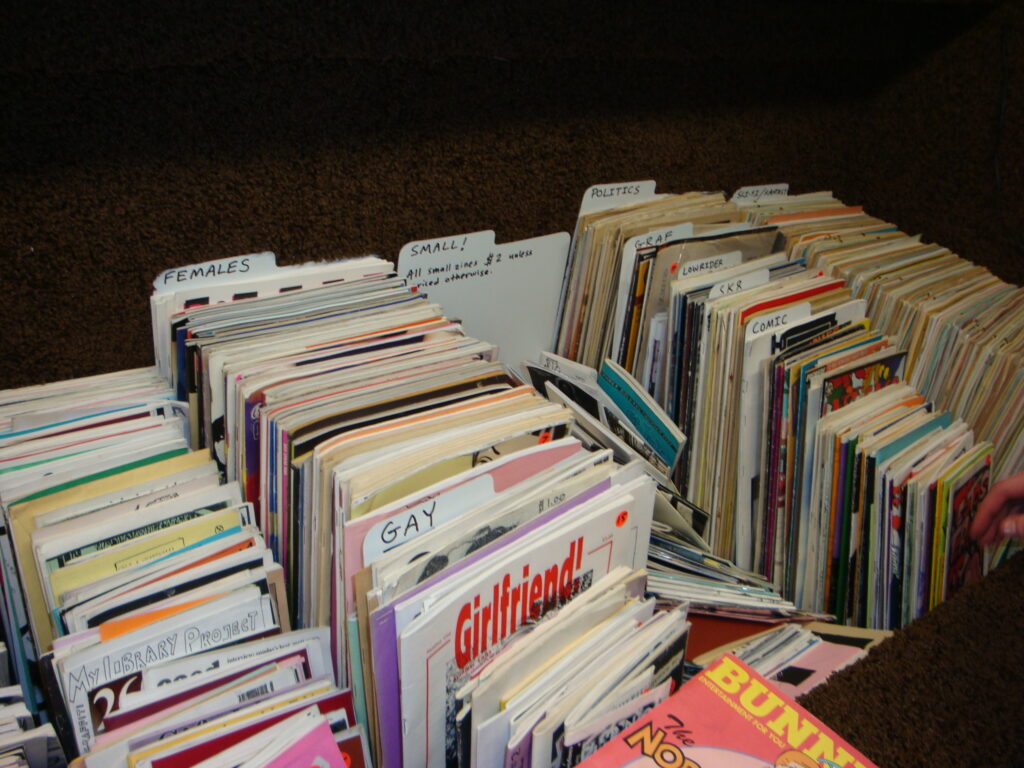

Punk subculturists traditionally often communicated through printed and physical publications, such as zines, where direct exchange between the creator of the zine with readers was common (Debies-Carl 2015). Access to these forms of communication was dependent on location and resources, and zines often had slow reaction times to subcultural events like new albums. Although zine creators often attempted to steer away from creating zines for money, many did struggle with the costs of printing, and online punk communication became popular. With a lower barrier of entry, the internet makes scenes more open and accessible to many actors, including people with genuine interests in the subculture, authorities interested in regulating the subculture, and corporate actors seeking to profit from subculturists. The internet may, however, also have a greater power to undermine some of the radical nature of subcultures and defuse their original messages because of this accessibility.

In the digital age, subcultures are also especially likely to be influenced by online interactions, which may include a greater focus on algorithmic content, curated images of the self, and marketing of products through apps and websites. As subcultures enter online spaces, the vulnerability of social media and internet groups to marketing may become more prevalent. Short and surface-level videos and images of subcultures and their imagery may also present a view of that subculture that focuses more on appearances, and particularly products, than the content and meaningful interactions that may occur in in-person interactions. Additionally, the short-form nature of social media allows for context collapse (Marwick & boyd 2010), where all potential viewers of media collapse into one, resulting in a lack of interpersonal interactions and ability to speak selectively. The Internet has also experienced a rise in aesthetics, which are labels that categorize a particular style, but do not necessarily correspond to cultural experiences, social networks, or shared values in the way that subcultures often do (Giolo & Bergman 2023).

Commodification can also serve to bring subcultures, and potentially beliefs associated with them, into greater power. This can increase the prevalence of not just members of subcultures, but their associated ideology. This is particularly true for subcultures with right-wing ties that may be promoted on social media (Miller-Idriss 2020).

Digital networks have the potential to act as both public and private, and using the internet has a price. Historically, the internet has experienced an overall shift towards privatization and away from more shared spaces. Some exclusively online subcultures, such as ones devoted to particular video games, require subscriptions as well as software to engage with other players. Subculture members that upload in-person subcultural activities, such as parkour (Kidder 2012), are at the mercy of the social media that they use to upload and whatever marketing tactics it employs. This overlap results in a shared ownership of online subcultural content between the creators and the host (Coleman & Dyer-Witherford 2007).

Jeffrey Debies-Carl, 2015, “Print is Dead: the Promise and Peril of Online Media for Subcultural Resistance.”

This article discusses the advantages and drawbacks of the shift within the punk subculture from primarily printed media and communication to online media. Namely, it mentions the ease of entry to online subcultures compared to the creation or purchase of printed zines. The ability to more easily publish subcultural content with the internet comes with advantages in reaching more people, as well as decreasing financial barriers to printing zines, but takes away some of the subcultural aspect of direct correspondence, trading, and social interactions that often occurred around zines. Additionally, the increased audience for subcultural content allows more people to be involved, but also exposes the online spaces of the subculture to marketers, authorities who wish to monitor subculturists, and potentially, others who wish to change or harm the subculture.

Ryan Moore, 2005, “Alternative to What? Subcultural Capital and the Commercialization of a Music Scene.”

In this article, Moore argues that the commercialization of subcultures affects subcultural capital by threatening the authenticity of subcultures and their participants. When companies co-opt trends from underground culture, they market it to the mainstream, reaching a wide audience of consumers. The subculture then ceases to be “cool,” losing its authenticity when people are unable to distinguish posers from original fans. Moore illustrates this process using the example of how the aesthetics of grunge and alternative music were turned into commodities by corporations, encroaching on the subcultural capital and authenticity of participants.

Max Horkheimer and Theodor Adorno, 1987, “The Culture Industry: Enlightenment as Mass Deception.”

In this important chapter from Dialectic of Enlightenment, the authors introduce the idea of the culture industry. Horkheimer and Adorno argue that popular culture mass-produces media that is used to manipulate society into passivity. While these scholars propose a more pessimistic view of culture, it is relevant to consider how the culture industry fuels the commodification of subcultures.

This documentary from 2001 shows the deliberate marketing strategies done to appeal to teenagers, including through subcultural imagery and items perceived to be outside of the mainstream.

Buchanan, Ian. 2018. A Dictionary of Critical Theory, 2nd ed. Oxford University Press.

Clark, Dylan. 2003. “The Death and Life of Punk, The Last Subculture,” pp. 223-36, in David Muggleton and Rupert Weinzierl (eds.), The Post-Subcultures Reader. Oxford: Berg.

Coleman, Sarah, and Nick Dyer-Whitterford. 2007. “Playing on the Digital Commons: Collectivities, Capital and Contestation in Videogame Culture.” Media, Culture & Society 29(6). https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443707081700

Connor, C. and N. Katz. 2020. “Electronic Dance Music: From Spectacular Subculture to Culture Industry.” YOUNG 28 (5): 445–464.

Debies-Carl, Jeffrey S. 2015. “Print is Dead: the Promise and Peril of Online Media for Subcultural Resistance.” Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 44(6). https://doi.org/10.1177/0891241614546553

Gaea, Laiken. 2015. “Oh My Goth: The Commercialization of Goth as a Subculture.” Sociology Theses & Senior Projects, Whittier College.

Giolo, Guilherme, and Michaël Berghman. 2023. “The Aesthetics of the Self: The Meaning-making of Internet Aesthetics.” First Monday, 28(3). https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v28i3.12723

Haenfler, Ross. 2023. Subcultures: The Basics. 2nd ed. New York: Routledge.

Hebdige, Dick. 1981. Subculture: The Meaning of Style. Taylor & Francis Group. Methuen. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203139943

Kidder, Jeffrey. 2012. “Parkour, The Affective Appropriation of Urban Space, and the Real/Virtual Dialectic.” City & Community 11(3): 229-253. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6040.2012.01406.x

Kosut, M. 2006. “An Ironic Fad: The Commodification and Consumption of Tattoos.” Journal of Popular Culture 39(6):1035–1048.

Liptrot, Michelle. 2014. “‘Punk Belongs to the Punx, Not Business Men!’ British DIY Punk as a Form of Cultural Resistance.” Fight Back: Punk, Politics, and Resistance. 232-251. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1mf700m.19

Marwick, Alice, and danah boyd. 2010. “I Tweet Honestly, I Tweet Passionately: Twitter Users, Context Collapse, and the Imagined Audience”. New Media & Society 13(1): 114-133. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444810365313

Miller-Idris, Cynthia. 2020. “Defending the Homeland.” pp. 93-110 in Hate in the Homeland: The New Global Far Right. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Moore, R. 2005. “Alternative to What? Subcultural Capital and the Commercialization of a Music Scene.” Deviant Behavior 26 (3): 229–252.

Schouten, J. W. and J. H. McAlexander. 1995. “Subcultures of Consumption: An Ethnography of the New Bikers.” Journal of Consumer Research 22(1): 43–61. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2489699

Spracklen, K and Spracklen, B. 2014. “The Strange and Spooky Battle over Bats and Black Dresses: The Commodification of Whitby Goth Weekend and the Loss of a Subculture.” Tourist Studies, 14(1):86-102.

Page Citation: King-Levine, Parris, and Jules Wood. 2024. “Commodification.” Subcultures and Sociology. Retrieved [date viewed]. (https://haenfler.sites.grinnell.edu/commodification/)