BACKGROUND

Gyaru is the umbrella term for to refer to a fashion subculture in Japan which has lasted for two decades. The subculture itself is divided into many subcategories: kogyaru, hime gyaru, ganguro, banba, yamanba. However, the core style orientation for identification remains stable: hair dyed in light color like brown or blond, heavy make-up, sexy clothing, and a wild attitude. Some scholars consider the birth of gyaru as a result of Japan’s unstable economic condition after the Japanese Bubble period in which stock market price was heavily inflated. But gyaru subculture is also a reflection of social class interactions through fashion styles.

HISTORY

“The gyaru totally came out of nowhere” – Yasumasa Yonehara, one of the first to discover the fashion subculture gyaru, in an interview with W. David Marx.

The beginning of the 1990s marked the first wave of gyaru subculture, kogyaru, when people started noticing an emergence of a large number of school girls from rich private schools with “brown hair, short schoolgirl skirts, and slightly tanned skin clutching European luxury bags and wearing Burberry scarves.” In the context of Japan’s financial crisis after inflation, kogyarus mostly consists of girls from the upper class who had accumulated wealth and were able to afford highly-priced clothing. In other words, Kogyaru luxurious everyday style can be explained by their desire to display a status of style leader through their ability to buy fancy Western fashion items.

These kogyarus were actually previously known as girlfriends of chiima or involved in chiima’s circles. Chiima, also called “teamers,” are Japanese youth from top private schools. These teamers mainly come from privileged backgrounds, but squander their money in throwing parties nights after nights. As Japan started tightening its law enforcement on night club scene, chiima ended up as only a short-lived movement. Kogyarus, on the other hand, started expanding their influence.

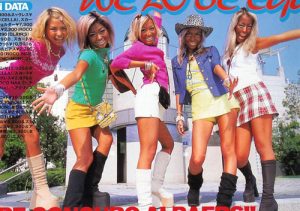

For first generation of gyaru that is kogyaru, the school uniform was a piece of personal clothing rather than something mandatory. Kogyaru would wear their uniforms everywhere after school. Adjusting knee-length skirts to mini-skirt, wearing “loose socks”, having a light tan, and dying their black hair are ways through which they rebelled against dominant norms on what a high school girl should look like. These acts of upgrading their uniform outfits are also how kogyaru embrace their youth.

Kogyaru reached its first peak in mid-1990s when it received extensive coverage from mass media which generated a moral panic by linking sexualized versions of uniforms that these girls wore to a deviance from the national character of morality. Also, Japanese’s shūkanshi, a kind of weekly provocative tabloid, heavily exploited this sexualized image of high school girls as the new sexual objects for older men men, establishing a stereotype and associating Kogyaru with teenage prostitution (known as ‘enjo kosai‘ in Japan) (Kinsella 2013). However, despite getting caught up in the stereotype, kogyaru did not make up the majority of teenage prostitution. It was in the midst of misconception of kogyaru and kogyaru themselves’ receiving harassments due to the prior issue that gyaru as a subculture took on their first transformation: ganguro.

The birth of ganguro as a prominent sub-genre of gyaru subculture was in the intersection between the significant decrease of the original wealthy kogyaru and the rise of lower-class gyaru participants. In this era, which was after mid-1990s, the subculture’s shift to a “cheaper” stylishtic direction happened. Ganguro girls’s dominant style involves heavy tanning in dark shades, bright or white face make-up, and hair dye in colorful color like gray, green… They also adopt speech considered vulgar and inappropriate for young women by society. The aforementioned stereotype and the way it drew older men to kogyaru contributed to the formation of ganguro as a defense mechanism of these subculturers to shut men out of their circle and instead focus on gaining favor from fellow participants of the subculture.

Kogyaru and ganguro are two major peaks of the subculture as a whole in terms of popularity and media exposure. Nevertheless, new subcategories of gyaru also arise through time while still keeping the stylistic core of the subculture.

Gyaru subculture is dominated by females, especially young girls. However, there are also male participants, who are called gyaru-o. Gyaru-o started appearing afterwards as they are mainly boys who are interested in gyaru girls and want to hang out with them. Gyaru-o’s lifestyles are also aligned with those of gyaru girls: deep tans, dyed hair, and frequent party sessions.

Themes

Resistance

At the root of the gyaru subculture is the common theme of resistance through fashion innovations and adjustments. In other words, the birth of the subculture is a reaction against the dominant Japanese culture up to the 1990s. Kogyaru sub-genre, the first generation of gyaru, is a way for high school students and young adults female to resist against dominant culture’s ideology on ideal physical appearance of women, as well as strict school rules and standards.

Afterwards, ganguro, still aligned with the resistance against dominant standards, seemed to focus more on resisting against the foreign influence. You can only witness authentic gyarus in Japanese neighborhoods. “This was a concrete step in Japan finding pride in its own domestic, non-designer fashion — overcoming the constant dull pain of an inferiority complex towards style originators overseas.” Furthermore, ganguro, by creating their own sense of identity instead of striving to resemble upper-class population, also frees itself from the class-based consumer culture in Japan.

Social class in gyaru subculture

The class-based nature of gyaru subculture can be seen through the variety of its subcategories because it allows participants from different social classes to join. At the very first form of gyaru, kogyaru, the subculture mostly comprises of upper-class high school girls and some middle-class girls. This is because this subcategory centers around materialism. Specifically, for one to become a kogyaru at that time, one has to first be able to afford expensive pieces of clothing. So firstly, kogyaru is only known practiced among affluent kids. However, as time goes, gyaru’s heavy exposure to the public through media channels because of the moral panics it has caused allows for the subculture’s dissemination within female working class in Japan. Shibuya 109, considered the hub of the gyaru subculture, also helps much in this process as it represents the commercialization of gyaru. Shibuya 109 is a shopping complex that has many gyaru clothing and accessories shops. In some senses, Shibuya 109 serves as a style guide for gyaru newbies. With gyarus more frequently flocking to the location, the shop owners started producing individual clothing pieces, usually flashy and sexy, for gyarus to mix and create their own gyaru outfit. No more confined to only high school uniforms, gyaru subcultures gradually becomes more accessible. Prices of clothings from these shops also vary greatly, so it caters and attracts not only gyarus from upper class but also those from lower class.

Reproduction

Another factor that also helps maintain the existence of this fashion subculture is its own transformative nature. Gyaru as a subculture has various sub-genres: from kogyaru, hime gyaru (an exaggerative and costly feminine style of kogyaru with excessive use of pink/pastel colors, laces and bows), to more extreme forms like ganguro, yamanba (even darker tan and more dramatic make-up than ganguro). Gyaru subculture never dies down, but rather moves to different stages signified by different styles and make-up. Some also attribute these transformations of the subculture as a way for it to stay deviant, since too many followers of a sub-genre will make it become normalized. As a result, going through radical changes of styles and class compositions is necessary for the participants to stay “different”.

Media

Interviews

Yasumasa Yonehara, editor of Japanese magazine egg, discussing gyaru subculture in today’s context.

Gyaru Interview – Japanese Kuro Gyaru Unit Black Diamond in Shibuya (2012)

An interview with leaders of a group of gyaru participants in the sub-genre of strong kuro gyaru ( dark skinned). These members of the group talked about the fashion, the culture, and more.

Documentaries

Japanorama Season 03: Bad Girls Gyaru (2009)

A BBC Choice Program that explores Japan’s current popular culture. Kogal, a sub-genre of gyaru subculture is featured (among some other subcultures) in the three episodes of season 3 of this program.

Japanorama – Season 3 – Episode 6 (youtube.com)

Significant Scholarships

Articles

Marx, W. David. 2012. “The History of The Gyaru.” Neojapanisme. Retrieved October 9, 2016.

Books

Kinsella, Sharon. Schoolgirls, Money,and Rebellion in Japan. New York: Routledge. Interaction of girl’s street fashion and how masculine journalism and subcultures in Japan center on the fetishistic image of young girls.

Kinsella’s article in Bad Girls of Japan specifically look at gyaru subculture in relation with races, especially when gyaru’s signature make-up style has certain resemblances to the act of blackface, which degrades African American’s racial identity.

Kinsella’s article in Bad Girls of Japan specifically look at gyaru subculture in relation with races, especially when gyaru’s signature make-up style has certain resemblances to the act of blackface, which degrades African American’s racial identity.

Other resources

Beck, Christian K. 2007. “There is a Stranger Among Us: The African-American Experience of Blackness in Japan.” MA thesis, Department of Anthropology, University of Cincinnati, Ohio. A thesis that involves taking into account the gyaru subculture and how African-American community experience the way blackness is portrayed in Japan.

Angelaka, Evdokia. 2013. “Disciplining the Japanese Body: Gender, Power, and Skin Color in Japan.” MA thesis, Department of Asian Studies, Lund University, Lund. A thesis that discusses how gyaru subculture of Japan, especially ganguro, raises some interesting questions on the meaning of skin color in Japan.

Ivanova, Adriana. 2012. “Facing Japaneseness: Becoming the Ethnic Other through Gyaru Self-Transformations.” MA thesis, Department of Media Studies, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam. A thesis that focuses on the ethnic meaning of the subculture itself.

Valdimarsdóttir, G. Inga. 2015. “Fashion Subcultures in Japan: A multilayered history of streetfashion in Japan.” BA thesis, Department of Japanese Language and Culture, University of Iceland, Reykjavík. A general overview of the subculture through time.

Page contributed by Quynh Nguyen