Overview

As meanings are made in a subculture (through environment, ideals, rules, clothing, norms, objects of significance), it becomes easier to define what is considered deviant, loosely defined as breaking a social norm or law, or as a failure to obey group rules. Stigma is constituted through labeling a particular group as deviant, typically done by people in power (i.e. government officials, lawmakers, media). Using deviance to create stigma is known as social control, an important aspect in analyzing the relationship between subcultures, race, and deviance (Becker 1966).

Race is one of the ways we identify ourselves and each other in society. One’s racial identity depends on a number of factors, including but not limited to their family history, cultural practices, language, and physical appearance. While there is no biological basis for race, we have learned to attach racial meanings to various physical and behavioral attributes. Race has varied throughout time and across location. For example, “in the early twentieth century, US law did not consider Italians, Irish, and other light skinned groups “white”” (Haenfler 2014:65). Ethnicity is another way with which we may identify. Like race, ethnicity has to do with family history, cultural practices, language, and physical appearance. However, ethnicity is used to described more specific subsets within race. Whereas race may refer to being white or black, ethnicity may refer to nationality, religion, cultural background, or a combination of those.

Racism is used to describe the belief that one’s own racial identity is superior to that of another, along with the attitudes and behaviors associated with it. Race and racism are embedded in and maintained by social institutions. Typically, racism functions along power dynamics, meaning that marginalized racial groups cannot be racist towards more dominant ones in society. White supremacy is the belief that white people are superior to others of different racial categories (particularly the black people) and that as a result, they should dominate society. Racism in the US relies on a white racial frame that provides “an overarching and generally destructive worldview, one extending across white divisions of class, gender, and age” (Feagin 2013:10). This framework consists of historical narratives of race, deep-seeded emotions, and selective memories, all of which are important to white Americans (Feagin 2013). It functions as a lens through which we view ourselves, others, and all of society. Racial segregation is the systematic separation of people based on race. While racial segregation has been established and enforced by law before in the US, it is now more common for individuals of different races to self-segregate. This is a result of historical legacies of racial discrimination.

Race is intimately involved with gender, class, sexuality, and other identity categories in society. The term ‘intersectionality’ is used to describe this phenomenon. Popularized by critical race theorist Kimberlé Crenshaw, intersectionality was initially used to shed light on the experiences of Black women (1989). Scholars like Crenshaw note that Black women experience sexism differently from White women, and that they experience racism differently from Black men. Now, intersectionality is applied to all different kinds of identities in order to give a more well-rounded account of anyone’s social experience. For example, in “Triple Entitlement and Homicidal Angers: An Exploration of the Intersectional Identities of American Mass Murders,” Eric Madfis interrogates the aggrieved entitlement of white, straight, middle-class men as the motivator of violence in recent mass killings (2014).

Deviance and Race

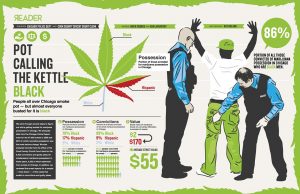

Deviance is heavily dependent on race, especially when it comes to crime and the justice system, for example a white-male from a middle-class area is less likely to be apprehended and less likely to go further into the justice system (i.e booking, conviction, jail time), than a black-male from the “slums” (Becker 1966), indicating dominant society’s inherent bias in considering acts committed by people of color to be more deviant than acts committed by their white counterparts (Becker 1966). This idea of deviance amplifying ideas of racial stereotypes and bias is an important factor in why an all-black-subculture is perceived as more criminal than an all-white-subcultures. Institutional racism in the criminal justice system oppresses communities of color by utilizing the biased framework of deviance. White and Black communities have roughly the same rate of drug use and abuse with the black community reporting one percent higher drug abuse and whites with one percent higher in drug abuse and dependance (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration 2013). However, blacks are still arrested for drugs more than two times their percentage in the population. In addition, black youth are twice as likely to be arrested for any crime compared to white youth, federal prosecutors are twice as likely to file for a mandatory minimum sentence for African Americans than whites for the same crime, blacks are more likely to receive longer sentences than whites, etc (National Academy of Science 2014). These are some of the ways institutional racism in the criminal justice system continues to build the black community as criminal and deviant, framing actions by the black community as inherently more deviant than their white counterparts.

Gangs and Deviance

Local and national gangs are all-black subcultures who’ve been labeled as deviant and forced into the role of criminal organization via several social control attempts by the government. The history of gangs in the US begins around the 1760s in New York with a group of European immigrants, with a spike in gang activity starting around the 1820s. During the 1910s, there began an increase in majority African-American gangs (Lopez 2012). The first African American gangs formed in response to an increase in discrimination from the white community and the police.

For example, during the 1910’s cities like Chicago, New York, Cleveland, and Detroit experienced a large migration of blacks from the south in search of jobs. In these cities there were gangs of white youth already established, in response to the discrimination and harassment of these white-youth gangs, black gangs started to form but were lacking strength in numbers (Lopez 2012). With civil unrest, poverty, and police terror on the rise all-black gangs started to value solidarity. Groups like the Black Panthers were driving factors in spreading the sentiment of unity to overcome adversity across the nation. With groups like this creating social backlash and attempting to make social change, the government made racialized attempts to destabilize this group via police terror, legal battles, and the political assassination of Fred Hampton, in doing so the government forces these groups into the toll of criminals by labeling gang activities as deviant, and playing on already stigmatized identities such as social class to portray black gangs as criminal, dangerous, and needing of control.

Different state governments and national governments attempted to inhibit the growth and impact of groups like the black panther party by defining many of their actions as deviant. By labeling certain actions as deviant there becomes a divide between the white dominant culture and black subcultures, it creates a dynamic of white being viewed as just and superior while framing blackness as deviant and violent (sagepub).

According to Emile Durkheim, if the government and dominant culture continue to label gangs and their participants as deviant, violent, and criminal then they will be forced into the deviant role, further enforcing the dominant hierarchy and keeping the minority culture suppressed. With the government forcing gangs and their participants into the deviant role it becomes substantially easier to control the group’s action and influence by only allowing the dominant culture to view gangs in the light of deviance. Overall, subcultures that are majority black are now perceived as deviant and criminal because of the history of social control by the government, entailing labeling gang activity as deviant, creating a racial divide, keeping the minority impoverished. Gangs, to youth, still represent brotherhood and support but have been tainted by the stigma received due to government control of their actions.

Music and Blackness

Many genres of music in popular culture today, although adopted by the public, originated through Black Subcultures. Within these genres of music exist different subcultures that have different notions of authenticity through class, gender, and location. Hip hop, for example, began as a cultural movement among African Americans and Latino Americans in New York City in the 1970s (Harrison 2008). Before grasping national attention, Hip Hop was a representation of blackness with historical and cultural meaning. However, Hip Hop subculture was viewed as deviant and therefore stigmatized by mainstream society. Members of the original Hip Hop subculture were often African American and Puerto Rican and at the time, they did not fit into society’s parameter of “normalcy” (Haenfler 2017). Deviance stems from the public’s reaction and as an unfamiliar form of behavior, the introduction of Hip Hop did not result in welcoming reactions and was thus labeled deviant (Becker, 1974). Hip hop was a black art form used as a language to communicate life struggles (Berkson 2017). As a tool of collective resistance, participants of the Hip Hop subculture saw their membership as a claim of “urban citizenship” in letting the general population conscious of their presence on a macro level (Black 2014).

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ar7sKNb4UUE

Today, due to globalization, the Hip Hop subculture has been commodified to sell blackness in the global market (Collins 2006). The very behaviors performed by African Americans that were labeled as deviant during Hip Hop’s rise are now glorified when performed by white people.

While subcultures provide the opportunity for individuals to challenge racial norms, many scenes are dominated by racial majority groups. As such, “people of color often carve out their own place within white-dominated scenes” (Haenfler 2014:67). One such scene is the Punk scene. The Punk subculture revolves around punk rock music, a genre defined by its loud, fast-paced, and angry sound. Often considered the epitome of adolescent rebelliousness, Punk and its spaces are typically dominated by white men. While women responded to this by creating Riot Grrrl in the early 90’s, various racial majority groups co-opted Punk for themselves. African Americans have been a part of the Punk scene from its beginnings. However, the Afro-Punk subculture is a direct response to white-dominated scenes. Afro-Punk attire is similar to that of punk (dark, tattered pants, band tees, piercings, tattoos, etc.) while incorporating other styles and influences, as evident in Afro-Punk festivals around the U.S., Europe, and South Africa. Bands that are associated with Afro-Punk include Death, Pure Hell, Rough Francis, and Crystal Axis. As punk spouts resistance and and anti-establishment politics, Afro-Punk provides a space for individuals to do so while addressing racism within and out of punk (Spooner 2003; Ensminger 2010).

Media and References

Media

Documentary “Bleaching Black Culture” (2014) discusses the role of black culture in forming American culture and the evolution of Hip Hop.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fanQHFAxXH0&feature=youtu.be

Documentary “Afro Punk: The Rock and Roll N**** Experience” (2013) examines the lives of black identities in the punk scene.

Documentary “Black Panthers: Vanguard of the Revolution” (2015) is the first full length documentary to discuss the Blank Panther Party’s impact on American culture.

YouTube clip in which Lord Lamar (actor and rapper) differentiates between white people liking black culture and white people liking black people.

YouTube interview of Common (rapper) in which he claims that although Blacks and Latinos created Hip Hop, you don’t have to “be from the ghetto to express Hip Hop.”

References

Bard, T.J. (2014). “The Study of Deviant Subcultures as a Longstanding and Evolving Site of Intersecting Membership Categorizations”. Springer Science and Business Media.

Barnes, M. P. (2008). Redefining the real: Race, gender and place in the construction of hip-hop authenticity (Order No. AAI3306059).

Becker, H.S. 1974. “Labeling theory reconsidered,” pp. 3-32 in Messinger, Sheldon The Aldine Crime and Justice Annual. Chicago: Aldine.

Berkson, S. (2017). Hip hop world news: Reporting back. Race & Class, 59(2), 102-114.

Black, S. (2014). ‘Street music’, urban ethnography and ghettoized communities. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 38(2), 700-705.

Collins, P. H. (2006). New commodities, new consumers: Selling blackness in a global marketplace. Ethnicities, 6(3), 297-317.

Crenshaw, Kimberlé W. 1989. “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics.” University of Chicago Legal Forum 1989: 139-167.

Ensminger, David. 2010. “Coloring Between the Lines of Punk and Hardcore: From Absence to Black Punk Power.” Postmodern Culture 20(2).

Feagin, Joe R. 2013. The White Racial Frame: Centuries of Racial Framing And Counter-Framing. 2nd ed. New York: Routledge.

Fraley, T. (2009). I got a natural skill?: Hip-hop, authenticity, and whiteness. Howard Journal of Communications, 20(1), 37-54.

Haenfler, Ross. 2014. Subcultures: The Basics. New York: Routledge.

Hagan, John. (2006). “Profiles of punishment and privilege: secret and disputed deviance during the racialized transition to American adulthood”. Springer Science and Media.

Harrison, A. K. (2008). Racial authenticity in rap music and hip hop. Sociology Compass, 2(6), 1783-1800.

Lopez, Antonio. (2012). “In the Spirit of Liberalization: Race, Governmentality, and the De-Colonial politics of the original Rainbow Coalition of Chicago”. University of Texas.

Madfis, Eric. 2014. “Triple Entitlement and Homicidal Anger: An Exploration of the Intersectional Identities of American Mass Murderers.” Men and Masculinities 17(1): 67-86.

Spooner, James. 2003. “Afropunk: The ‘Rock n Roll Nigger’ Experience.” YouTube Video. Afro-Punk Films. (https://youtu.be/fanQHFAxXH0).

Page by: Helena Alacha, Enrique Rueda, Ernesto Nanetti-Palacios