Background Theory

The field of philosophy defines the term ‘authentic’ either in the strong sense of being “of undisputed origin or authorship”, or in the sense of being “faithful to an original” or a “reliable, accurate representation” (Varga & Guinon 2017). In the realm of sociology, authenticity plays a paramount role in how individuals construct and portray their identities especially in a given subculture. Vannini and Williams (2009, pp. 3) postulate that “authenticity is not so much a state of being as it is the objectification of a process of representation, that is, it refers to a set of qualities that people in a particular time and place have come to agree represent an ideal or exemplar.” The individual defines authenticity, and it is even further defined by the observer who sets the criteria for greater meaning within a relative context. For instance, the common propensity to describe a cuisine as “authentic” has no inherent meaning. We often create this meaning based on how we perceive it as representative of a culture, place, or group of people. Subculturists create authenticity, and judge others, often without acknowledging the power it has to transform one’s place or status within a group. They also construct authenticity in a variety of ways and through the accumulation of what the prominent sociologist, Sarah Thornton, terms “subcultural capital”.

Subcultural capital consists of the knowledge of the scene, possession of relevant physical objects, appearance through style, and perceived commitment or longevity of identification with the scene (Thornton 1995; Force, 2009). Subculturists attempt to find their own sense of identity that is unique to the overarching internal values of their scene. Thus, authenticity is a process that is malleable in terms of context–both time and place. However, ideas and representations about authenticity can morph into a hierarchical system of inclusion and exclusion that may delineate between individuals who adhere to the ideals of a subculture and those who display a more established sense of individuality and clout within a given scene.

Since authenticity is a process and changes meaning depending on the observer, it also changes in relation to larger societal shifts, such as increased marketing or commodification of the elements of a subculture that make it “cool”. Subcultures lose their sense of resistance and authentic edge, per say, when they are commodified and presented to the mainstream society. For instance, the retail store Hot Topic arguably commodifies subcultures by spreading elements of subcultural capital, particularly clothing and accessories, to a mainstream consumer sector. This process enables a wider audience to capture a specific style that might be associated with the punk subculture, for example. Commodification, in turn, drives innovative subcultural shifts in ideology or criteria for subcultural capital, thus perpetuating a constant desire for subculturists to perform authenticity in their respective scene.

Individuals perform authenticity across many different subcultures, but is markedly evident in music subcultures such as punk and hip-hop. Authenticity is often marked by elements of identification such as gender, race, and socioeconomic status. For instance, it is often true that women and girls must exert more direct efforts to perform authenticity due to a lesser representation in male dominated subcultures like punk and hip-hop. In these scenes, we can observe how elements of identity and methods of self-representation influence perception of the music, artist, or genre in general, and how the subculturists perceive identity as a measure of authenticity.

Punk

Punk has undergone tumultuous changes since its emergence in the late 1970s. Punk transformed from a socially isolated tribe to a commercially profitable trend by the mid-1990s, and many of the core values, including style, DIY ethic, and politics became muddled as the subculture appeared in the mainstream. Even before punk fell into the eye of mainstream consumers, participants in the punk subculture continually try to prove their authenticity, ranking themselves according to their own status hierarchy, and distinguishing themselves from the ‘poseur’ (Haenfler 2013). Within the punk subculture, the Straight Edge punks would develop their own displays of authenticity unique to their scene. Of the ways punks convey their authenticity, two avenues of expression seem most important: Style and Music.

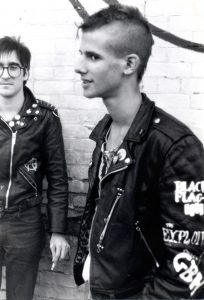

The punk look became a recognizable set of signifiers used to set oneself apart from the mainstream (Cogan 2017). Force (2009) writes that the most blatant method for aligning oneself with a subcultural group is sartorial adornment (Force 2009). Punk dress served simultaneously to signify membership in a subculture, solidarity with other punks, and disaffiliation with mainstream culture (Leblanc 1999). Dress and appearance are vastly important within many subcultures. In Punk, style became a form of conspicuous consumption. Punks could choose to adapt mainstream commodities to create a sense of punk identity. The commodities are adapted and changed so they are not based on any kind of ‘uniform’ and instead cultivate a punk identity (Ewen 1988). Baggy overcoats were as punk as leather jackets and flight suits. Most important in terms of authenticity is the creation of disparate styles, allowing the wearer to self-identify as punk. Tied to punk fashion are the importance of familiarity with music and other visual displays of identity (Force 2009). The practice of wearing band T-shirts and displaying unconventional style, such as Mohawks or JBF hair, are examples of how punk style becomes an embodiment of authenticity. Within the Straight Edge scene, participants use markers to denote themselves a part of a subculture. Such markers include marking their hands with a black ‘X’, transforming the symbol of underage kids into a badge of defiance (Haenfler 2013).

Apart from style and appearance, perhaps the most important marker of authenticity in punk is possession of subcultural capital in the form of physical and immaterial goods. In many subcultures and the punk scene especially, subculturists must continually prove their authenticity or risk being labeled a ‘sell out’ (Haenfler 2013). A way subculturists prove their authenticity is through amalgamation of what Sarah Thornton calls subcultural capital (Thornton 1995). Subcultural capital comes in many forms, including material objects such as band T-shirts and vinyls, and in mannerisms, style, and speech (Haenfler 2013). Examples of subcultural capital include the rare T-shirt, the special edition vinyl, the knowledge of which bands are hot. In the punk scene, musical taste and knowledge of an acceptable punk “canon” are paramount (Cogan 2017). Similar to the heavy metal subculture, musical taste is very important in the scene. Physical possession of the ‘right’ music becomes a way one legitimizes themselves within the scene (Force 2009). Many discussions occur in the punk scene concerning what is accepted in the canon, and punks use this opportunity to flex their relevant knowledge. Punks frequently question others about their knowledge of the scene in order to test authenticity. Haenfler (2013) says “the point is that members of subcultures continually assess authenticity and therefore deliberately create ways to communicate their authenticity (Haenfler 2013 Pp. 41). The role of these discussions is to determine the ‘poseurs’ and the ‘sellouts’ from those who truly identify with the punk demographic.

Hip Hop

Originating in the African American communities of the Bronx in the 1970s, hip-hop branched out to other major cities in the United States such as Los Angeles, Seattle, and Houston. After gaining popularity in America, the genre traveled around the globe (McLeod 1999). The original four elements of hip-hop included breaking, tagging, DJ-ing, and MC-ing. In the 1990s, hip-hop broke into the mainstream culture as sales grew over the years, generating $700 million in revenue in 1993, expanding from $100 million in 1988. White teens consumed hip-hop’s products while MTV and BET displayed the music on their channels. The subculture had joined the mainstream, and authenticity became a topic of discussion (McLeod 1999). Today, hip-hop has become one of the highest grossing musical genres. Globalization has allowed for fans to participate all around the world.

Authenticity is threatened by the potential for assimilation to the mainstream culture. Within the genre, authenticity discourse arises around the controversy of every artist sounding alike and repeating similar words and phrases (McLeod 1999). The idea of authenticity within hip-hop stems from staying true to one’s identity while also sharing or representing a background in low class struggle, frequently described as “keepin’ it real” or some variation of the phrase. Yet, an artist can reach mainstream popularity while also remaining authentic. The artist must continue to produce the style of music that helped them reach popularity, rather than selling out and producing music simply for the sales. Kendrick Lamar and Chance the Rapper, two prominent hip-hop artists sitting atop the charts while earning countless awards and worldwide recognition, still have not deviated from the styles on their original mixtapes in 2004 and 2011, respectively. They continue to rap about the issues of race and other problems faced in lower-class communities. Anthony Harrison, a well-known author whose work revolves around the many facets of participation in hip-hop, explains that authenticity comes from “staying true to yourself rather than following the mass trends, being underground as opposed to commercial, and originating from the streets not the suburbs” (Harrison 2009).

Harrison’s work also introduces the idea of race and that authentic hip-hop comes from blackness while, fake rap sells out from its connotations to whiteness. Yet, many prominent emcees have been white, most notably Eminem, and they have gained underground legitimacy without completely adopting the style and vernacular of black emcees. This example complicates the connection between whiteness and a fake style of hip-hop, and racial authenticity may not take as much precedence as other aforementioned factors (Harrison 2009). Rather, relation to class, revolving around the lower-class/poverty, is the major signifier of authentic hip-hop. Rap music arose from the lower-class setting, therefore music coming from and speaking of this lifestyle is viewed as more authentic (Hodgman 2013). White artists like Eminem, Bubba Sparxxx, and Machine Gun Kelly have been able to rap authentically of their lower-class upbringings. The prominence of drugs, violence, and an overall difficult life situation blur the lines of race and move towards the distinction of class for authenticity.

Authenticity also develops through the representation of the lower-class via musical lyrics. Staying true to yourself requires one to produce or perform an accurate representation of themselves without distorting any part of their life histories or conforming for the mass consumers. The musical lyrics of the rap/hip-hop scene must display an accurate portrayal of the emcees own environment, no matter how grim or violent (McLeod 1999). Additionally, if blackness correlates with a more “real” expression of hip-hop in the scene, artists then cater their music more towards black audiences. By not completely associating their work with whiteness, it limits the possibility of the “selling out” claim.

There is a dichotomy between the underground and the commercial aspects of the music scene. Underground artists appear unknown to the mass consumers, while authentic listeners follow these individual’s underground careers. Artists like Immortal Technique, MF Doom, Atmosphere, and Hopsin lead the underground hip-hop scene but do not rank highly on listings of artists by public sales. These underground rappers perform at small hip-hop clubs which seat around 1,000 audience members rather than massive stadiums and concert venues that hold tens of thousands of people. Going commercial typically signifies both selling out and conforming to creating music that the public wants to hear, and which sells in waves depending on mainstream popularity. There is also a gendered aspect as “selling out” is associated with being soft and feminine. A “hard” and masculine artist creates music that men want to hear, instead of catering towards the feminine audience by incorporating more melody and pop aspects. When going commercial, a rapper no longer independently distributes music, but rather decides to join the large music industry. Their music enters the media outlets of radio and television rather than underground hip-hop clubs. Authentic emcees view the Grammy’s and other popular award shows negatively, as they reward certain artists for their abilities to produce music for the general, mass listener (McLeod 1999). These shows represent the largest community of common listeners, with the board members mainly consisting of upper-class, wealthy, white individuals, considered inauthentic based on the identity criterion mentioned previously. In recent years, artists

considered non-authentic, namely Drake (lived a fairly wealthy and struggle free childhood) and Macklemore (white) have taken home multiple Grammy awards.

Additionally, males comprise much of the hip-hop genre. Alongside the dominant male ideal is the dominant, straight male ideal. Gender and sexuality define a “real man” in the hip-hop scene. Over the years, there have been almost no gay rappers, making the subculture appear homophobic. The small amount of prominent, female emcees also shows the importance of a male within the genre. Whether a female is gay or straight, there is little room for one. Listeners want to hear the words from a male, as it sounds much less authentic when spoken from a female perspective (McLeod 1999).

An expansive knowledge of both hip-hop history and scholarship is the most frequently used method of subcultural capital in the genre. An individual can claim to be more authentic to the genre simply by having the ability to recite an abundance of historical hip-hop facts including prominent artists and tracks, feuds and battles, and the years when certain events occur (Harrison 2009). For example, these individuals would know Tupac and Biggie died in 1996 and 1997, OutKast’s Speakerboxxx/The Love Below has sold the most copies of any album, and Ice Cube’s not from Compton. Additionally, owning and purchasing hip-hop artifacts differentiates participants from one another. The non-authentic may simply listen and own a few relatively new CD’s while the more authentic have a large collection of 12-inches and have been collecting CD’s for decades.

Page created by: Sam Galanek, Anthony Gulve, and Mimi Sarai

Media

Hip Hop:

This song touches on the idea of the realness of hip-hop, and that there are not many artists remaining who are truly authentic. Jay-Z claims to still be creating authentic rap music.

- Eminem – “White America” (2002)

This song brings up the commercialization of rap music, especially to white, “suburban” kids who would never have heard the true “authentic” black rap music. The consumers, who make up the middle and upper classes, only listened to Eminem because they shared the same skin color.

Logic, currently a popular rapper of mixed racial background, speaks on the concept of authenticity in modern rap. He focuses on the way artists change their persona to assimilate to what is popular and how these changes are viewed by other “authentic” rappers.

Director Connie Chavez follows The Garden, an underground hip-hop group formed in the birthplace of the musical genre (NYC), through their musical jourmey. She speaks on the group’s ability to create music for the sole purpose of “the love for the music” rather than for fame and economic success in the mainstream markets.

Punk:

- Punk’s Not Dead: Punk Rock Documentary Los Angeles 2016

A documentary following the re-emergence of backyard punk scene in Los Angeles. The work includes discussion of what makes punks ‘punk’ in this scene.

- Trying it at Home: A Documentary on DIY Punk.

A documentary on the DIY ethos of Punks. Self-identified Punks discuss the importance of DIY to their own Punk identity.

A step by step guide of how to fit into the punk scene, even if you don’t adhere to the pillars of punk subculture. An example of the mainstream commodification of punk style.

Green Day discusses claims made against them, calling them sellouts and ‘Rockstars’. Explicit.

A documentary examining the roots of the underground, hardcore punk scene in New York. This provides many insights to the Authenticity practiced in the punk scene.

Books

Haenfler, Ross. 2014. Subcultures: The Basics. New York: Routledge.

This work offers a holistic introduction to subcultures through sociological theory and a substantial body of research. It details main concepts of subcultural studies and includes Haenfler’s personal experiences in the field of sociology.

Leblanc, Lauraine. 1999. “Pretty in Punk”. Rutgers University Press.

Leblanc, Lauraine. 1999. “Pretty in Punk”. Rutgers University Press.

Leblanc’s Pretty in Punk combines autobiography, interviews, and analysis to create an insider’s examination of the ways punk girls resist gender roles and create strong identities.

Thornton, Sarah. 1996. Club Cultures: Music, Media, and Subcultural Capital. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press.

This book contributes to sociological work that studies youth in subcultures, and more specifically in terms of concepts related to authenticity and identification.

Vannini, Patrick and J. Patrick Williams. 2009. Authenticity in Culture, Self, and Society. Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing Co.

Vannini, Patrick and J. Patrick Williams. 2009. Authenticity in Culture, Self, and Society. Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing Co.

This book includes contributions from a variety of prominent sociologists who share their perspectives on the concept of authenticity from a sociological lens.

Articles

Force, William R. 2009. “Consumption Styles and the Fluid Complexity of Punk Authenticity.” Symbolic Interaction, 34(2): 289-309.

Handler, R. 1986. “Authenticity.” Anthropology Today 2(1): 2-4.

Harrison, Anthony. 2009. “Claiming Hip Hop: Race and the Ethics of Underground Hip Hop Participation.” Pp. 83-119 in Hip Hop Underground: The Integrity and Ethics of Racial Identity. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Hodgman, Matthew. 2013. “Class, Race, Credibility, and Authenticity within the Hip-Hop Music Genre.” Journal of Sociological Research, 4(2): 402-413.

Lindner, Ross. 2001. “The Construction of Authenticity: The Case of Subcultures.” Pp. 81-90 in Locating Cultural Creativity. London; Sterling, VA: Pluto Press.

McLeod, Kembrew. 1999. “Authenticity within Hip-hop and Other Cultures Threatened with Assimilation.” Journal of Communications, 49(4): 134-150.

Moore, Ryan. 2005. “Alternative to What? Subcultural Capital and the Commercialization of a Music Scene.” Deviant Behavior, 26(3): 229-252.

Varga, S. and Guignon, C. 2017. “Authenticity.” The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

William, J. Patrick. 2006. “Authentic Identities: Straightedge Subculture, Music, and the Internet.” Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 35(2): 173-200.