Skating, originally referred to as ‘Sidewalk Surfing’ emerged in 1958 as southern Californian surfers found a way to mimic surfing on land. They discovered that by using a small wooden board with metal roller skate wheels, they could make smooth turns on the sidewalk. “Smoothly paved schoolyard banks also served as endless asphalt waves on which to practice surf maneuvers” (Vivoni 2009). Although skateboards began to be mass-produced and sold in stores beginning in 1962, they were still very primitive and many people made their own. These homemade boards, often equipped with clay wheels, led to many injuries, and in 1965 skating was deemed a dangerous fad by the media.

A groundbreaking moment for skating occurred in 1972 when Frank Nasworthy invented urethane wheels. These wheels rode much more smoothly and safely. In fact, they were so successful that urethane wheels are still used on skateboards to this day. Another revolutionary moment for skateboarding occurred in 1978, when Alan Gelfand invented a skateboarding trick called the ‘Ollie’ (Adelman, 2). This trick is still probably the most recognizable skater term, and was the foundation of many tricks to follow.

There are two primary types of skateboarding: vertical skating and street skating. A group of skateboarders called the zephyr team (Z-Boys or Dogtown-Boys) originated vertical skateboarding, often referred to as vert skating, in the ’70s. “‘Dogtown’ describes the depressed, lower-middle class, south Santa Monica neighborhood that witnessed the birth of contemporary skateboarding. The “Z Boys” (not all of whom were boys) are the twelve members of the original Dogtown skateboarding team, a group of unsupervised Santa Monica preadolescents in the mid-1970s who convened around and then were sponsored by the local Zephyr surf shop and who went on to revolutionize the sport of skateboarding.”(Roth 2004) They did this by discovering that they could skate in an emptied out pool. This manmade arena with smooth walls offered new opportunities for experimentation and creativity that the flat ground of the streets could not provide. Although the original Z-Boys consisted of men who went on to become famous skaters including Tony Alva, Stacy Peralta, and Jay Adams, it was Tony Hawk, not a Z-Boy, who broke the boundaries of skating by launching out of the side of an empty pool into the air. This redefined what skateboarding had the potential be and raised the ceiling of what people imagined they could do on a skateboard.

In an attempt to make this platform more accessible “a poor man’s version of the pool was developed by skateboarders who didn’t have access to good pools or skateboard parks. The ‘ramp’ was a ply-coated two-by-four-framed structure that mimicked the transition and lip of backyard pools” (Transworld 1999). Although street skating remained more accessible and more widely participated in, media attention and international competitions made vertical skating more visible. Media continued to bring attention to the scene in the 1980s, and although skateboarding’s popularity took a dive in the early 1990s, it came back in a wave accumulating attention and popularity to become what it is today, a global, multibillion-dollar industry (Donnelly 2008).

In this video Tony Hawk briefly explains how to do arguable the most famous skater trick, an Ollie. He uses a board to demonstrate a step-by-step process with his hands and then gets on the board show what the trick looks like when all the components are put together.

This video illustrates how the first wave of skateboarding evolved, and the fundamental role the Z-Boys played in its revolution.

Riding a skateboard has been associated with danger, carelessness, and laziness and skaters are marginalized more than people who chose to ride bicycles, scooters or rollerblades. Skateboarding is not only a means of travel or even just a sport. As a subculture, skaters value creativity, risk, and freedom. Whereas traditional sport is organized and run by adults, skateboarding is not. There are “no referees, no penalties, no set plays. You can do it anywhere and there is not a lot of training” (Beal & Weidman 2003). Within skateboarding comes the space to make decisions, challenge oneself, and not have to abide by strict guidelines about what is acceptable or how to be successful. Within the skating subculture, like most subcultures, there are hierarchies of authenticity. These hierarchies coincide with prevalence of skater values. For example street skating could be viewed as more authentic because “compared to skate parks, street skating is considered more real and cool – requiring courage and creativity” (Adelman, 7).

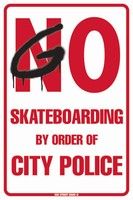

There is a disconnect between the creativity and empowerment that skateboarders express and the fear and judgment of skaters expressed by people outside of the subculture. For one, although skateboarders participate in vertical skating in constructed spaces such as skateparks, they participate in street skating in ‘found spaces’ (Johnston 2016). Skateboarders tend to seek out new places to skate, especially where they are prohibited to be skating. This is part of what adds to a skateboarder’s deviant image. As they use public spaces to experiment, grind on benches, jump staircases, do tricks over garbage cans, there is the perception that public property could get damaged. In addition, media created ads that “ appealed to masculine risk-taking and the teenage sense of immortality often depict death-defying skateboard stunts” (Beal & Weidman 2003). Media molded public perception and fear shaped peoples’ attitude toward skateboarding. “Negative public attitudes such as these marginalize skateboarders as being ‘risky’, ‘devious’, and ‘unsavory’” (Johnston 2016).

Compared to organized sport there is minimal parental guidance in skateboarding in addition to a great chance of physical injury. This combination creates an image of deviance and enforces the value skaters place on freedom and risk. “These ideals of freedom and risk are integrally linked with D.I.Y. (do it yourself) culture. Street skaters are often portrayed or refer to themselves as being ‘self‐made’; this D.I.Y. ideal purports that skateboarding is a socially democratic enterprise where individuals can freely participate and construct unique styles, practices and identities” (Atencio 2009). Onlookers and outsiders feel fear due to a lack of control over skater practices.

Another important value to the skater subculture is lack of competition. Competitiveness is even an indication of not being authentic as a skater. Skaters value pushing themselves to do their best and not directly comparing themselves to others, believing that this encouraging environment fosters more enjoyment. As Beal and Weidman (2003) write, “embracing the central values of the subculture participant control, self-expression, and a de-emphasis on competition-was essential to the authenticity of a skateboarder.” Although, this value and distinction are becoming increasingly complicated with time as events such as the X-Games are popularized and skateboarding becomes a more profitable mainstream sport. Competing in large scale competitions, being judged on specific criteria, and winning money all go directly against skater values of intrinsic motivation and lack of competition. “Skaters struggle to maintain these core values while enjoying the legitimacy that comes from professionalism” (Catin-Brault 2015). In contrast, big time skating competitions, such as the X-Games, promote the sport and provide exposure which captures the attention of a larger audience and causes an increase in potential newcomers. Many professional skaters find it hard to speak against these competitions because they directly benefit from the exposure in being able to successfully live off of what they do, even if it is not being true to the essence of what skateboarding used to be. Catin-Brault claims, “The cynicism that was once at the core of skateboarding has now been transformed into a ‘cool edge; that perpetuates the unfreedom of being a slave to the dictates of ideology”. One way in which a skater can enjoy the perks of media and competition while still maintaining their authenticity is to consciously specify their motivation and continue to display their passion in situations where there is no external reward.

One of the most iconic skateboarders of all time, Tony Hawk, was touring the world as a professional skateboarder, making six figures, with sponsors and fans when he was still in his teens. In an interview with CNBC, he emphasizes how he stuck with skateboarding in the 1990s when the rest of the world did not. He states, “I always felt skating was so sacred to me and the people who did it, especially in the days where it wasn’t cool and it was just what we had to do” (Edwin 2012). In speaking about skating in this way, he ensures that his motivation is known to be pure and intrinsic, based on his love for skateboarding and not for external motives such as money or fame.

Another famous skater, Rodney Mullen, helped give the Ollie a lot of its fame as well as inventing another popular skateboarding trick called the ‘kick flip’. Whereas Tony Hawk is famous for his vertical skating, Rodney Mullen is famous for street skating. The two professionals speak to one another in a video, demonstrating many values of skater culture in just a short interaction. Hawk states, “you and I bounced tricks off of each other. I remember you watched me do an airwalk and then you were like oh psh I gotta learn that and then you go and do it on the flat” and Mullen responds without hesitation, “and likewise I would do a trick and then see you do it in vert, like fingerflips and I would just like… like oh my god, he’s doing that in pools and I’m having problems on the ground… and it would be so inspiring for me” (RIDE Channel 2012). This interaction illustrates the camaraderie, de-emphasis on competition and the laid back attitude that authenticate skaters embody. By displaying these qualities, professional skaters who engage in competition and rely on cooperation, brand, and media support are able to remain true to skater values and remain admirable figures in skater culture. As you can watch in the video below, Tony Hawk’s humble demeanor, guts to try new things, inspiration of creativity, and relentless drive to accomplish new goals, even with his billion-dollar worth and big-time status, allow him to remain an authentic skateboarding legend.

In this video Tony Hawk demonstrates his desire to continue to explore and innovate in the skating industry. He attempts a new trick with components of ‘do it yourself’, creativity, and danger. Doing so shows his intrinsic desire and passion for skateboarding in a context outside of competitions such as the X-Games in which there would be external motives.

This video is another demonstration of Tony Hawk sustaining his authenticity. The CNBC interviewer focuses on Hawk’s fame and fortune, questioning him about his incredible success. Hawk keeps bringing the the conversation back to his love of skateboarding, staying humble and downplaying his fame.

What do you think of when you hear the word skater? What image comes to mind? Have you noticed that no females have been mentioned thus far, that every video and photo on this page solely features men? If you did not that is because the typical participants are white males and we live in a male dominant society with great gender disparity. Although skaters practice a variety of forms of resistance to the mainstream, their resistance does not carry over to the patriarchal system of society. As skateboarders, women must work especially hard in order to gain acceptance and authenticity; otherwise they are viewed and labeled as ‘groupies’ or ‘skate Bettys’ and often perceived by male participants to be invested in skateboarding for alternative reasons. “Not only did the male skaters assume that females were looking for cool guys, but they also assumed that females were less physically capable” of skateboarding. (Beal and Weidman 2003) This is one way in which skateboarding is effected by intersectionality.

One way for women to be perceived as the ‘real thing’ is to become ‘one of the guys’. Beal and Weidman (2003) thought that the necessity to be like ‘one of the guys’, “indicated that masculinity was assumed to be the norm on which authenticity was evaluated. Females are not accepted as legitimate participants until they become guys.” Another way for women to be perceived as authentic is to display hyper sexualized femininity. Similar to how male athletes other sports get attention for their skill and accomplishments and women athletes of equal or greater merit get attention for their physical appearances, often male skaters get attention for their talent and female skates get attention for their hyper femininity. However, there have been more inclusion of female skaters over the years. This is especially true after skateboarding became an Olympic sport and obtained publicity. Even though skateboarding was “historically dominated by young men, it is now “increasingly popular with women.” (Bäckström and Blackman, 2022). Additionally, “a great many women participants in skateboarding are actively challenging the traditional gender dynamics of the sport, making space for nonconforming sexual or gender identities and pushing for inclusion in space traditionally dominated by teenage boys and adult men.” (Willing, 2019).

Skaters illustrate their authenticity to one another through a multitude of ways. Some of which are physical such as style and possessions. As skateboarding gains popularity these things become easier to mimic and style alone is not as distinguishable. Although there are strategies skaters will use such as looking at a fellow skater’s shoes to see if they are worn down and scratched up from skating. There are many terms that skaters know and use regularly that only hold meaning within a group of skaters. Because of this, they can identify authenticity through language and demonstrated knowledge of the culture. Not only daily jargon and expressions but also names of tricks, names of other skaters, places to skate, and knowledge of brands all demonstrate authenticity. Almost more important than knowledge and language is commitment and consistency. A skater’s “legitimacy is constituted by their daily engagement, as opposed to the outcome of an isolated event” (Beal and Weidman 2003). One aspect of authenticity that is relatively unique to skateboarding is that most of the reward is intrinsic. Beal and Weidman state, “people become involved in skateboarding and realized there was no inherent meaning in the activity, dropped out of skateboarding…those who quit skateboarding were the ones looking for a predetermined rebellious meaning”.

Another level of authenticity in skateboarding that is complex is between skater and industry. For a skating company to gain authenticity it needs to be backed up and usually needs the knowledge and collaboration of an experienced skater. For example, if a skater were to design their own shoes brings authenticity to themselves and to the brand they are designing for. Certain brands, such as Vans, have been in the skating industry since it’s beginning. Nike, a more mainstream sport brand has been attempting to get into the skating industry as it becomes more and more profitable. “Nike recently bought one of Vans’ local Orange County competitors, Hurley International Inc., a clothing company that targets skaters and surfers and that doesn’t yet make shoes.’’ In attempt to maintain their superior status as a go-to skater brand and to point a finger at where nike is weakest when it comes to authenticity, Vans created a commercial that emphasizes their longevity and dedication to the skateboarding industry.

This short clip features an 8 year old, female skater speaking about what skating means to her. “I want to show girls that they can skate.” – Sky Brown

This is a documentary that goes more in depth on skaters’ values and first hand experiences, as well providing great representations of how skaters dress and what a daily skate session might look like. It also does a great job at highlighting how skaters perform deviance and how society views and reacts to skateboarding culture.

Adelman, Howard, and Linda Taylor. “About Surfing and Skateboarding Youth Subcultures.” Center for Mental Health in Schools at UCLA, n.d. Web. Study examined history of skateboarding as well as characteristics of skaters and impact of skater subculture.

Atencio, Matthew, Becky Beal, and Charlene Wilson. 2009. “The Distinction of Risk: Urban Skateboarding, Street Habitus and the Construction of Hierarchical Gender Relations.” Qualitative Research in Sport and Exercise 1(1): 3-20. Web. Addresses distinctions between types of skating as well as the issue of gender.

Beal, Becky, and Lisa Weidman. 2003. “Authenticity in the Skateboarding World.” DigitalCommons@Linfield. Linfield College.

Beal, Becky. 1995. “Disqualifying the Official: An Exploration of Social Resistance through the Subculture of Skateboarding.” Sociology of Sport Journal 12(3): 252-67. Study in which 41 skateboarders were interviewed and demonstrated the juxtaposition of hegemonic as well as counter-hegemonic behavior as people engaged in both reinforcement and resistance.

Dinces, Sean. “‘Flexible Opposition’: Skateboarding Subcultures under the Rubric of Late Capitalism.” Grinnell College Libraries Journal Finder. International Journal of the History of Sport, n.d. Web.

Donnelly, Michele K. 2008. “Alternative and Mainstream: Revisiting the Sociological Analysis of Skateboarding.” Tribal Play: Subcultural Journeys Through Sport. Vol. 4. N.p.: Emerald Group Limited. 197-214. Study addresses skateboarding history as well as resistance, gender and competition’s effect on mainstream status.

Fok, C. Y. L. & O’Connor, P. (2021) Chinese women skateboarders in Hong Kong: A skatefeminism approach. International review for the sociology of sport. [Online] 56 (3), 399–415.

Johnston, Dan. (2016). “Skateparks: Trace and Culture.” Global Media Journal 10(1): n. pag.Westernsydney.edu. Web. Study of skate-parks’ role in youth culture through visual traces in different countries.

Vivoni, Francisco. 2009. “Spots of Spacial Desire: Skateparks, Skateplazas, and Urban Politics.” Journal of Sport and Social Issues: 1-18. SAGE Publications. Web. Discusses regulation and control attempts in skateboarding in urban settings.

Wall Street Journal article regarding Nike’s attempt to market to skaters. http://www.wsj.com/articles/SB1019596080451575280

Article discusses the Z-Boys at greater length.

https://muse.jhu.edu/article/55166

This page delves into the history of vertical skating.

http://skateboarding.transworld.net/features/vert-skating-101-a-history-lesson/#Xfwx3wFphMRJR02I.97

This webpage provides a concise timeline of skateboarding history.

http://teacher.scholastic.com/scholasticnews/indepth/Skateboarding/articles/index.asp?article=history&topic=0

Page citation

Subcultures and Sociology 2024. Retrieved [insert date viewed] (https://haenfler.sites.grinnell.edu/……..).