Leather subculture has been prominent within queer culture for over eighty years. For gay men in particular, shared interest in leather was an avenue for community building at a time when finding fellow queer people was difficult. While sapphic people have their own unique relationship to the leather community (and the closely related BDSM community), gay male leather subculture is heavily documented as an essential feature of sexual nonconformity.

Leathermen form a gay male subculture that eroticizes leather dress and symbols

Mosher, Levitt, and Manley (2006)

Leather subculturists self identify as ‘leathermen’, who, according to Mosher, Levitt, and Manley (2006), “… form a gay male subculture that eroticizes leather dress and symbols.” Gay leather culture originated in 1940s San Francisco, likely in response to the newly established motorcycle clubs in the post WWII era. These emergent clubs, which also gained traction in major cities like Los Angeles and New York City, were a reflection of queer people’s dissatisfaction with the oppressive nature of dominant American culture (GLBT, n.d.). Proper leather bars emerged about a decade later. In Chicago 1958, partners Chuck Renslow and Dom Orejudos established the first leather bar of its kind. The two would later develop and host the leather competition, ‘International Mr. Leather‘ (Fraser 2020).

While any performance of hypermasculinity may have been a protective measure taken by gay men to guard their queer identity, it was largely an authentic expression of gender and sexuality for this particular queer collective. Gay male sexuality as it is regulated by the heterosexual hegemon is conflated with femininity – consider how gay men are often caricatured in popular media. When gay male sexuality is inherently feminizing, masc and butch men are erased as the diversity of gay identities is lost in homogeneity. If subculture is understood as a symbolic form of resistance to cultural hegemony organized by an ‘othered’ group of people, leather culture maintained and strengthened the identity of a disempowered community within a disempowered community (i.e. stigmatized leathermen within the already minoritized gay community).

Radical queer communities and subcultures are founded on collectivism as a rejection of capitalist individualism that centers procreative sexual relationships. Capitalist culture also filters sexual ethics through traditional Christian values; the language of morality and piety is an equivocation about the material utility of heterosexual relationships for producing the next generation of wage laborers. Protestant complementarity theory suggests that men and women have separate essential values that complement each other (Foucault 1976). Obviously existing as queer was, whether deliberate or not, an act of defiance against these values. But, belonging to a subculture that centered sex meant above all that subculturists were participating in deviant practices for their pleasure. The ‘leather’ in gay leather subculture did not emerge because subculturists were looking for the best route of rebellion against dominant culture; rather, resistance to the status quo came as a result of living in accordance with their desires.

Marlon Brando in his iconic role in the film The Wild One is the inspiration for the aesthetic of leather culture. His character’s fashion staples were a leather jacket, leather boots, and most notably a Muir cap. Imitating Marlon Brando, who classically embodied normative masculinity, was both a display of appreciation for masculinity and an act of subversion of that rigid gender expectation (Loving 2020).

Photography from the 1950s-60s shows members of the subculture similarly outfitted to Brando – moto jackets, caps, fitted (typically leather) pants and hands gripping belts. This particular combination of posing and styling reads immediately as gay to other queer people. Queers who have developed the skill of reading can pull meaning from the world that other people cannot. This makes verbalizing queer desire unnecessary – a safety measure which has been crucial to the survival of queer folks throughout history.

Queer readers can also create meaning from symbols and artifacts that are not, on their own, overtly queer. While the following is not exclusive to leather subculturalists, leathermen used fashion to communicate their subcultural leanings without jeopardizing their safety by loudly outing themselves (Fawaz, 2018).

Every night there was the blackout. Ah, if you’ve never experienced one of the big cities with all the streets in total darkness, you really can’t imagine what it was like! For some reason it aroused me sexually—maybe it was just because I was young—but I would go out night after night and cruise the pitch black streets and look for sex. I was not the only one turned on. There were lots of other soldiers and sailors prowling in the dark. (Hooven, 2020)

-Tom of Finland

The artist Touko Valio Laaksonen, better known by his professional name, Tom of Finland, helped pioneer the aesthetic foundation of leather subculture. His work started getting attention at the height of censorship in the 1950s; Laaksonen had always been an illustrator, but returned to drawing consistently after WWII. During wartime, he relied less on fantasy to satisfy his desire for queer experiences when all around him sexual deviance was unregulated. For those serving in the military and separated from their wives and girlfriends, there was an understanding that men needed to fulfill each other’s desires. While gay men were less susceptible to punitive consequences during their service, post-war Finland did not have the same infrastructure that would enable cruising culture (requires ‘reading’) and allow for queer sexual freedom (Ferguson 2019). Again, Laaksonen was forced to protect his art and his sexuality in secrecy.

Robert Mapplethorpe was a prominent queer photographer in New York City’s gay bondage scene in the 70s and 80s. Some of his best work features men in leather attire practicing BDSM. He is well known for his decades long friendship – and five year long intimate relationship – with Patti Smith.

Tom of Finland inevitably began producing his illustrations again, featuring hyper masculine men with exaggerated musculature, often outfitted in skintight leather jodhpurs and jackets (a nod to biker culture) or a uniform of some kind, and always posed in ways that implicitly or explicitly signaled sex. The drawings were unapologetically erotic and provocative and regularly crossed the line into pornographic. Despite the sexual conservatism that characterized the social climate at the height of his career, Laaksonen embraced his deviant interests. This authenticity was a source of inspiration and hope for the longevity of queer subculture, which was particularly necessary for his many fans during the rise of the AIDS crisis. Going into the 1980s, Laaksonen noticeably moved away from the highly stylized illustrations he had been producing in decades prior to more realistic depictions of bodies, particularly of men he knew. The following is a collection of Tom of Finland’s work – most of which is courtesy of the Tom of Finland Foundation (ToFF) – arranged chronologically to demonstrate the evolution of his style.

The 1970s were a time of immense growth and specializations of the institutions of the leather community. There were many new bars, some with more distinct clientele, as well as new kinds of establishments like bathhouses and sex clubs that catered to the male followers of leather culture – but his new development did not stay unregulated for long. In the mid-late 1970s and early 1980s, law enforcement were looking for any opportunity to criminalize homosexuality and disrupt queer subcultural resistance. Police officers regularly raided establishments like bars, clubs, and bathhouses because these were the only spaces leathermen had to gather that were safe from the culturally normative majority. The rate at which law enforcement were targeting leather culture institutions was unmatched among gay community spaces. At the height of their persecution, leather subculturalists were given little to no support from the rest of the queer community. It was likely they were never aware that discriminative policing practices were being used to destabilize leather subculture because of the social distance between the dominant gay community and leathermen, but any association with leather would have threatened their safety too (Rubin, 1982).

By the time the AIDS crisis was at the forefront of the social consciousness, visibility of gay leather subculture was at a high. With gay men blamed for the emergence and spread of AIDS, leather subculture was vilified by association. This prompted the shift from the ‘Old Guard’ – the original model for leather subculture, now associated with sexual deviance in normative spaces – to the ‘New Guard.’ The Old Guard iteration was highly exclusive with particular rules of conduct from interactions with other leathermen to appropriate leather attire. The New Guard, however, had more relaxed rules and opened up to be more inclusive of non-white queers and trans men (Loving, 2020).

Leather subculture was originally a smaller subset of alternative gay culture, but it drastically increased in popularity in the 1970s when it became closely intertwined with BDSM. BDSM stands for Bondage/Discipline, Dominance/Submission, Sadism/Masochism. Leather features prominently in the sexual practices of many BDSM subculturalists: leather gear can bind and restrain during bondage play, certain leather garments can indicate a participants status as a ‘dominant’ or ‘submissive,’ and leather toys/implements can trigger certain sensations or inflict pain. Leather kinks and fetishes can also exist outside the realm of BDSM if the individual subculturalist is only interested in the material of leather. For those leather subculturists who also overlap with BDSM practitioners, wearing leather attire associated with dominance or submission is an optimal way to signal those combined interests publicly without further demonstration.

BDSM, like leather culture, is only acceptable when practitioners confine it to the private sphere of their lives, in the same way queer people are tolerable to the heterosexual public only when they decenter their queer identity enough to be convincingly sexless. Queerness in theory is palatable so long as it is invisible; the deviance inherent in queer sexuality is only excusable so long as queer people demonstrate their commitment to normalcy.

Queer people are in perpetual search of belonging because the messaging they have received throughout their lives has been that they cannot belong as they are. For homophiles – a group of queer people who advertised their ability to perform straight normalcy – the pain of lifelong othering moves them to uphold the assimilationist imperative. The genesis of queer activism in the 1990s challenged assimilationist movements that only slightly adapt the boundaries of sexual oppression to accommodate normative queers (Allen, 2023). For those who remain authentic to their varying degrees of sexual deviance, participating in communities organized around sex and founded on the values of mutual pleasure and collectivism is one way to cultivate a sense of belonging.

Radical queer communities and subcultures are founded on collectivism as a rejection of capitalist individualism that centers procreative sexual relationships. Capitalist culture also filters sexual ethics through traditional Christian values; the language of morality and piety is an equivocation about the material utility of heterosexual relationships for producing the next generation of wage laborers. Protestant complementarity theory suggests that men and women have separate essential values that complement each other (Foucault 1976). Obviously existing as queer was, whether deliberate or not, an act of defiance against these values. But, belonging to a subculture that centered sex meant above all that subculturists were participating in deviant practices for their pleasure, and understanding sex outside of the ethical bounds of Christian conservatism.

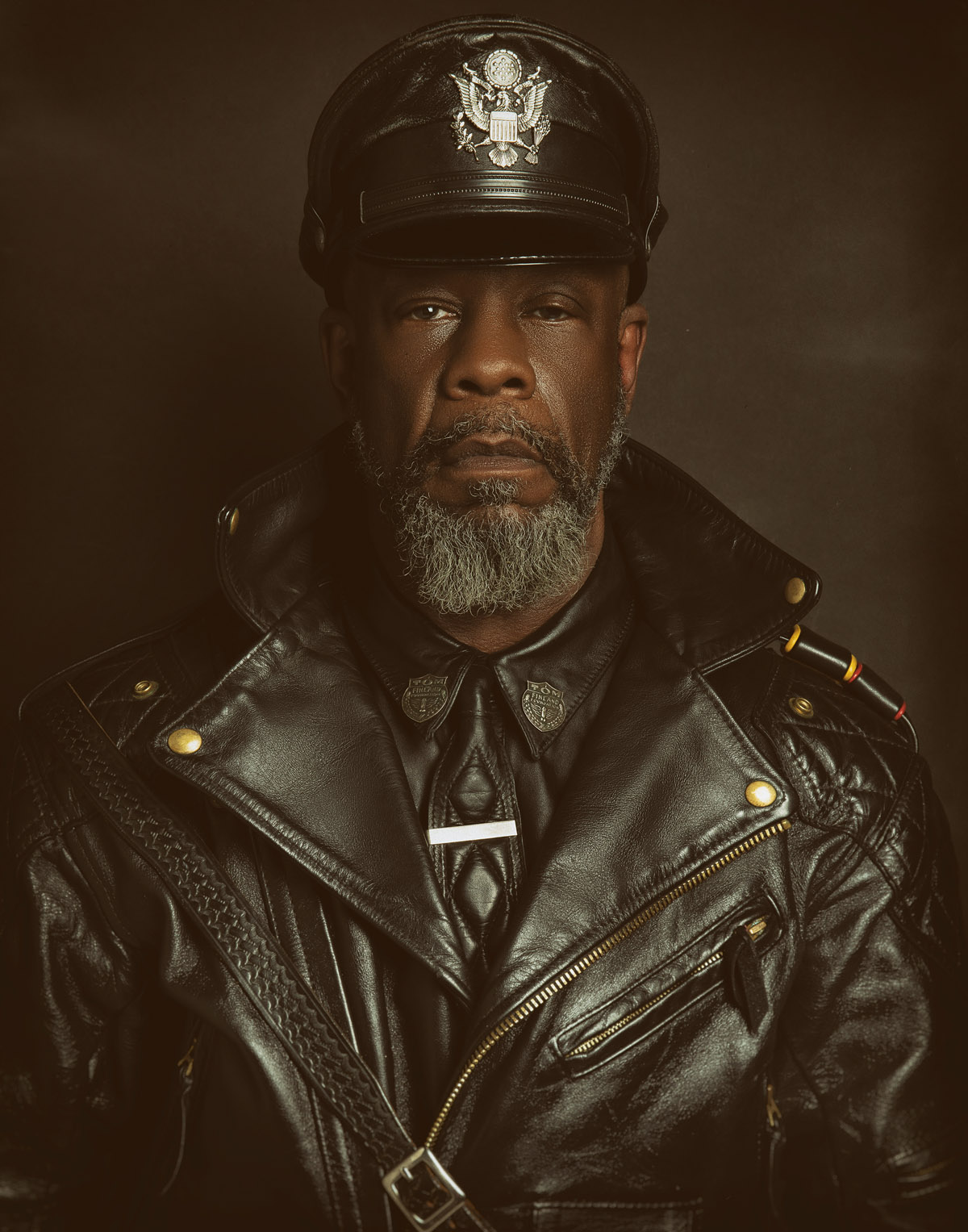

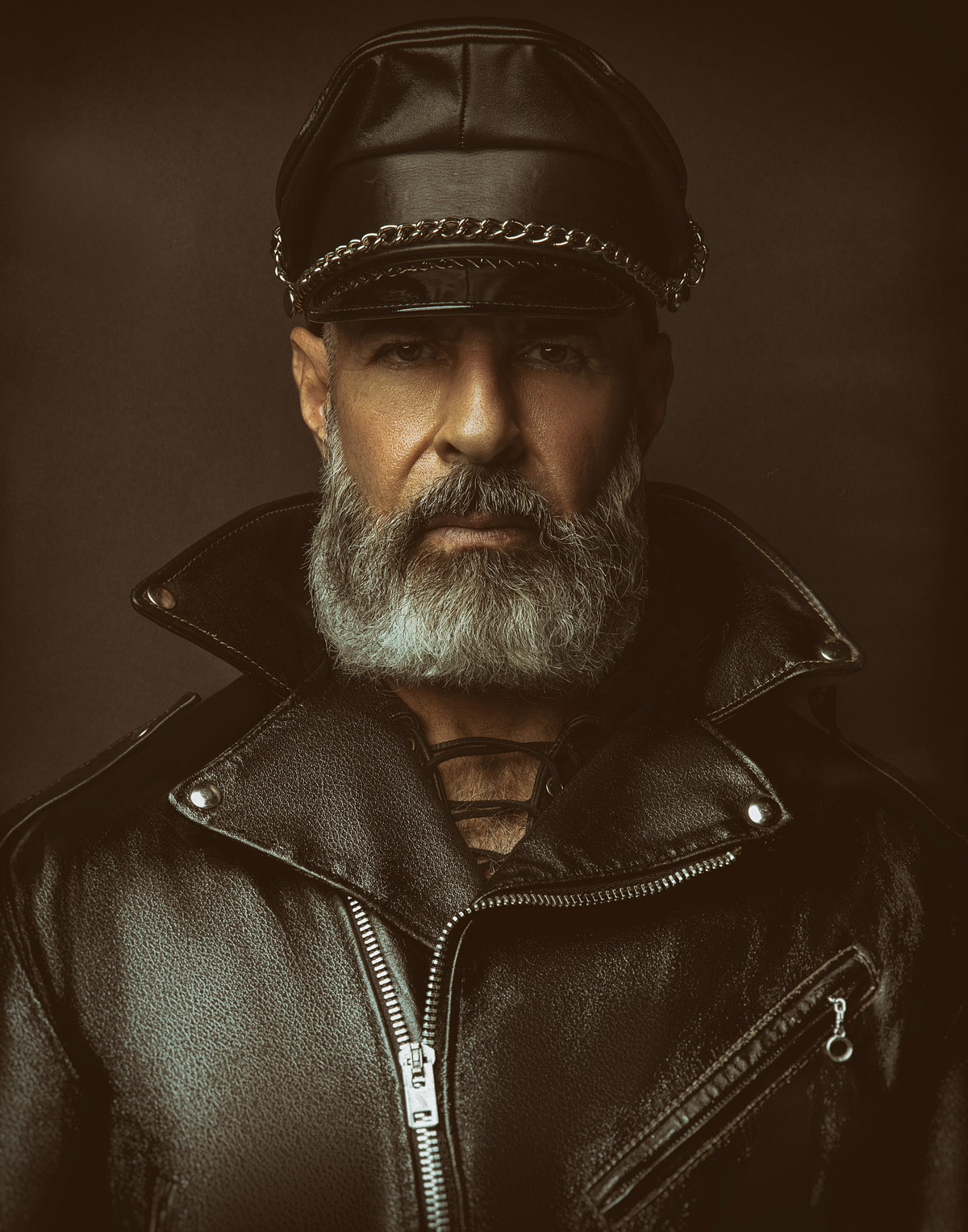

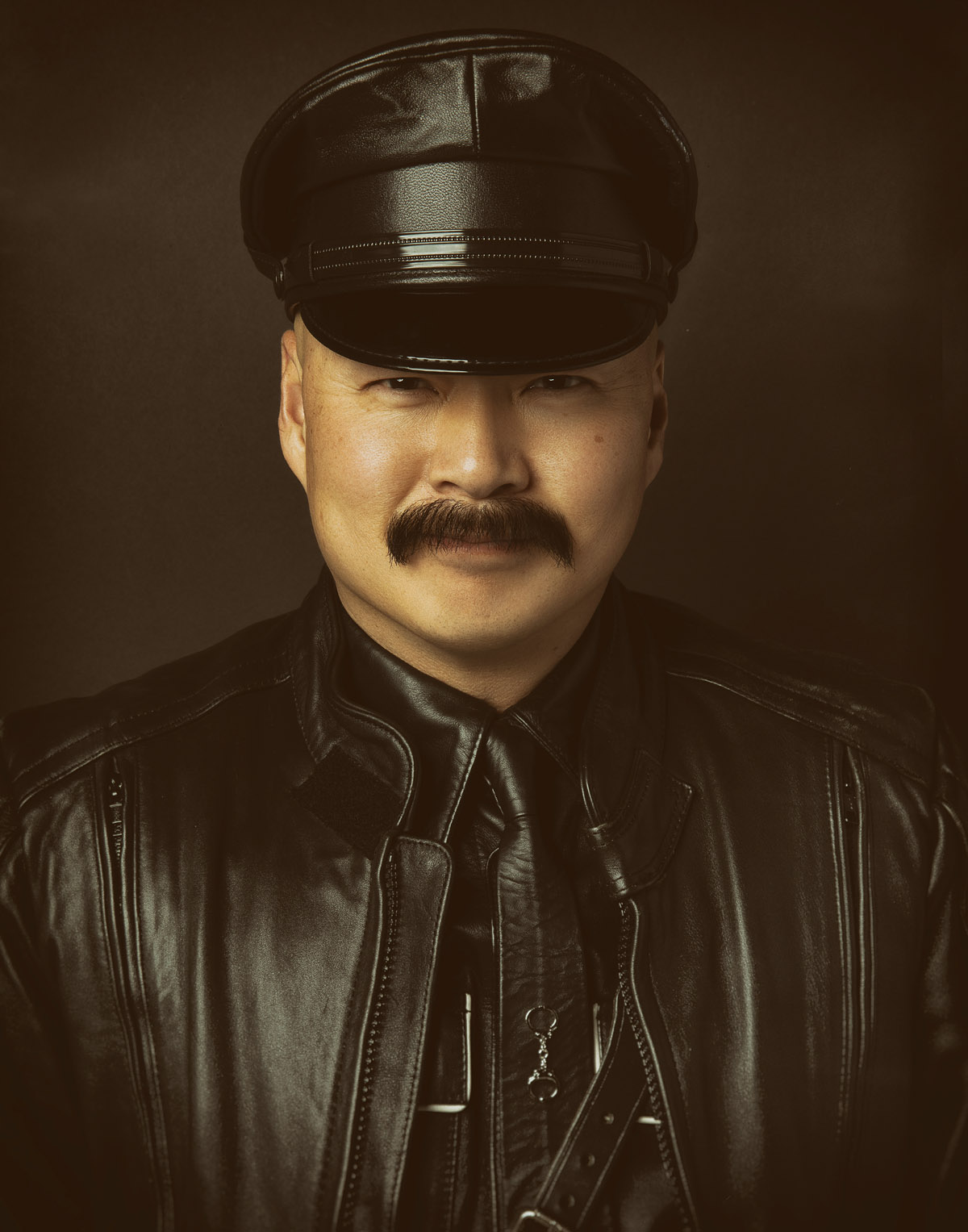

Leathermen at Gay Pride Parade in Manhattan, New York City

Leathermen at London Pride Parade

Leathermen of all identities on what leather subculture means to them

All courtesy of Mike Ruiz (2022)

Hale, Margaret. 2024. “Queer Leather Subculture.” in Subcultures and Sociology. Grinnell College. Retrieved Month Day, Year (URL).