The concept of elite deviance has a long history in the United States, beginning in the mid-1900s and continuing to the present day. In 1940, Edwin Sutherland established the concept and definition of “white-collar” crime. In his article “Is ‘White-Collar Crime’ Crime?”, Sutherland defined white-collar crime as “crime committed by a person of respectability and high social status in the course of his occupation” (Sutherland 1945). Shortly thereafter, in 1956, C. Wright Mills published The Power Elite, subsequently coining the term “the power elite” in reference to the military, corporate, and political elite (Mills 1956). In this account, Mills discussed the interlocking relationship of the power elite, ultimately enabling their success and rendering the ordinary citizen relatively powerless. Deviance perpetrated by the power elite for purposes of personal gain or power characterize the traditional conception of elite deviance. The notion of “elite deviance” has a longstanding and murky history, with no truly clear definition. Elite deviance entails a variety of criminal/deviant actions, including healthcare frauds, price fixing, and antitrust violations. As a result of its broad nature, scholars have often altered or manipulated the definition of elite deviance. However, there are certain key elements that remain constant, such as upper-class status. Perhaps, the most inclusive and helpful description comes from David Simon in his book Elite Deviance. Simon defines elite deviance as the actions committed by elites and/or the organizations they head that lead to physical, financial, or moral harm; these acts include economic domination, government control, and denial of basic human rights in order to experience personal or organizational gain in profits or power (Simon 1999).

Organizations frequently play a central role in elite deviance due to the arrangement of American institutions. First and foremost, American institutional structure is composed of “people whose positions within organizations have provided them the greatest amount of wealth, power, and often prestige of any such positions in the nation” — in other words, the power elite (Simon 1999). As such, the concept of elite deviance centers on individual or organizational offenders acting out of personal interest, organizational goals, or both (Simpson 2013). Second, because organizations hold a “shield of elitist invisibility,” elites are able to perpetrate deviant acts with relative ease. Consequently, those in power – the power elite – possess the capability to define deviance in their own terms, in ways that benefit their status positions. The power held by the power elite (social, political, and economic) yields the ability to influence ideologies and, subsequently, deviance, itself.

According to Alex Thio, those in positions of power and leaders of organizations are inclined to engage in deviant behavior for three reasons: (1) their goals are more challenging to legitimately achieve; (2) there are more opportunities for them to cheat on their taxes or steal from their company; (3) they experience weaker social controls (Salinger 2005). Essentially, as a result of structural complexities that render deviance relatively easy and the lenient penalties for elite deviance, individuals in positions of power are more likely to commit these deviant acts. Elite deviance is, at a basic level, the “violation and manipulation” of the standards for trust (Shapiro 1990). Ultimately, individuals and organizations establish their elite role on an imbalanced system of trust.

Furthermore, elite deviance is closely tied to the notion of the “American Dream.” Steven Messner and Richard Rosenfeld state in Crime and the American Dream, that the same values and behaviors that are viewed as part of the American Dream are also the underlying causes of crime in American society (Messner and Rosenfeld 2012). These values include: achievement orientation, individualism, and “fetishization” of money (Simon 1999). Essentially, the American dream means earning wealth. Moreover, some anomie scholars (scholars who study the breakdown of social bonds between individuals and communities) have argued that the American Dream means attaining more wealth than you currently have, meaning that greed is a given factor (Robinson and Murphy 2009). Acquiring this economic and monetary success has a long history of force and fraud in the United States. Individuals such as Al Capone, John Gotti, and Bernie Madoff exhibit the unabashed ownership of elite deviant behavior and the American Dream.

The topic of elite deviance is unequivocally a topic of social class and access to societal resources. Today, individuals in elite positions are predominantly members of the upper class; these individuals control or own a majority share in organizations, industries, finance, education, commerce, the military, communications, civic affairs, and law (Dye and Zeigler 1993). As a result, the conception of a “white-collar criminal,” for example, is different than that of a “common criminal” because their motives stem from different macro organizational and social processes (Benson and Moore, 1992). This is, in part, a consequence of the highbrow news presentation of criminal demographics; highbrow news present working class and unemployed individuals as criminal significantly more frequently than the upper class (Grabe 1997). Overall, the portrayal of criminality and deviance in the media is focused on non-elite members of society, and used to present corporate capitalism as a flawed, but ultimately superior economic system (A Theory of Elite Deviance). This perspective results in the perpetuation of a classist system that contributes to the previously mentioned ease of elite deviance perpetration.

In America, the history of elite deviance has remained relatively unknown to the general public. Simon briefly delineates the timeframe of awareness in Elite Deviance. He describes the public’s knowledge in three phases: the first wave, spanning the majority of the twentieth century, was characterized by general inattention to the problem; the second wave, from the late 1970s to the early 2000s, demonstrated a growing public knowledge toward upper class offenses, including increased sentiment toward the severity of elite deviance and crime; lastly, the third wave, occurring within the last fifteen years, entitled “transformed attention,” referencing the immediate accessibility of information and news coverage (Cedric, Cochran, and Heide 2016). The increasing awareness of elite deviance, and white-collar crime specifically, is significant because a greater understanding of the severity of such crimes leads to a higher likelihood of individuals condemn the actions of elite offenders. In “The Consequences of Knowledge about Elite Deviance,” Cedric Michel, Kathleen M. Heide, and John K. Cochran acknowledge that the eventual consequence of this greater attention could be both deterring white-collar crime and enacting stricter punishments on this type of crime – leading to a moral condemnation and retribution (2016).

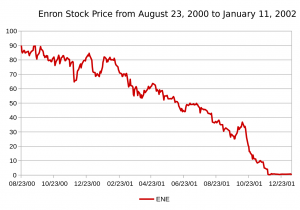

Throughout the past several years, well-known elite deviance scandals have plagued the economic world. For instance, the Enron et al. cases, which occurred between 2001-2002, were the first major white-collar crime case of the 21st century in America (Friedrichs 2004). Furthermore, in 2003, economic analysts estimated that price fixing cost the American public up to $78 billion per year (Salinger 2005). For instance, Bernie Madoff’s conviction on security fraud, money laundering, and nine other charges in 2009 cost his clients $64.8 billion. Total, the U.S. loses $426 billion to $1.7 trillion to white-collar crimes. Conversely, street crimes cost the United States around $179 billion in government expenditures. These three examples are only a small faction of the elite crime that has occurred, so far, in the 21st century. Returning to Mills’ concept of the power elite, the role of morality (“higher immorality”) is discussed; for Mills, wealthy and powerful members of society perpetrate higher immorality through unethical financial, political, and business practices, including violation of antitrust laws, corporate tax advantage, and certain salary practices (Mills 1963). Goals of power and profit can lead to situations where deviant/criminal behavior become permissible as a means of goal attainment (Chambliss 1989). As stated by Simon, “elites commit acts of great harm, often without knowing they are doing anything wrong” (1999). Therefore, elite deviance is fundamentally a form of deviance built upon a system of privilege.

The political arena displays one of the most obvious areas of privilege within elite deviance. Political corruption and crime are two examples of abuses of power that benefit from and contribute to the veil of secrecy surrounding powerful organizations, institutions, and individuals. At a basic level, political corruption and crime entail the use of political power for material gain and the fraudulent methods used to gain and maintain political authority (Simon 1999). In a more nuanced analysis of the political and governmental structure, the secrecy, deception, and abuses of power exhibited by government officials and agencies (i.e. the political elite) builds upon the notion of higher immorality to enforce existing structures of power and dominance in society. As a result of these structural inequalities, elite deviance occurs with relative ease and remains markedly under-acknowledged.

Despite growing public awareness of elite deviance and crime, this form of behavior remains relatively easy to commit. Additionally, individuals who commit elite deviance face limited effective deterrents, due to lenient penalties for such actions. The narrow presentation of elite criminality in the news enables the continued perpetration of elite deviance, allowing for the power elite to maintain a hold on the presentation of deviance in society. While the accountability structures seem to be shifting, the ingrained systems of power remain, thus enabling elite deviance to continue, regardless of the potential consequences. Looking to the future, however, a change in public perception of elite deviance appears to be occurring. With unprecedented frequency, high-power individuals are facing public allegations of crimes, as well as, incarceration, rather than benefiting from the traditional veil of secrecy and protection that previously surrounded their actions.

Since the 1980’s, bankers and stock brokers on Wall Street have been avid drug users. Popularized in the movie Wolf of Wall Street, cocaine became ubiquitous among the high-powered businessmen who were looking for a competitive edge in a cutthroat and stressful industry. As a stimulant, cocaine provided much-needed energy for those working upwards of 100 hours a week, needed confidence to close deals and needed to work more hours to separate themselves from their peers. In 2017, cocaine remains prevalent, but professionals on Wall Street abuse prescription pills like Adderall, Xanax, Vicodin and ecstasy to achieve similar effects and cope with the physical and emotional stress of their work environment. Most of these people must turn to the black market to obtain their drugs in such large quantities (some Wall Street executives claim to need 100 pills a day), and although these practices are widespread and well-known, there are few high-profile drug busts and this rampant drug abuse goes unchecked. Wall Street members accept this drug use as part of the work culture, and legal entities treat it as a health issue rather than one of criminality. If taken too far, “high-finance intervention specialists” like Robert Curry offer interventions to these businesspeople for $30,000 each. Dr. Nicholas Kardaras runs The Dunes East Hampton, “an exclusive rehab center for Wall Street’s addicts on Long Island where a full treatment regimen can run as high as $65,000 a month.” Despite these prescription drugs being controlled substances and Schedule 2 drugs in the state of New York, almost none of these Wall Street professionals face the 8-10 year jail time and accompanying fines that other offenders face. Meanwhile, economic and racial minorities are arrested on drug charges at much higher rates in New York. In addition, despite crack cocaine and cocaine in powder form being almost identical molecularly, the penalty is 18 times higher for crack possession than for cocaine possession. The connection between racial and socioeconomic of respective users of these drugs is, therefore, evident; poor minorities face harsh penalties than white elites for the same crimes. The shield of white collar privilege protects and obscures the drug use of Wall Street bankers and stock broker. As a result, the legal entities treat these individuals as patients rather than criminals.

In 2017, a long list of powerful white men in government and in Hollywood have been accused of sexual assault, sexual harassment, and rape. Allegations became more frequent after rising pressure against Hollywood executive, Harvey Weinstein. Over 80 women have accused Weinstein of sexual misconduct over the span of his career. On October 8, 2017, the Weinstein Company fired Weinstein and he entered a rehab program. Soon after, many women stepped forward against the likes of Senator Al Franken, Senate candidate Roy Moore, actor Kevin Spacey and a number of high-profile actors, comedians, businessmen and members of the media. While these disturbing accusations have come to light this year, they paint a picture of a common occurrence tracing back to the 1970s and earlier. As the powerful white elite, these men have used their power and influence to commit these acts and suppress the consequences. For example, despite accusations of molesting a 14-year-old girl in 1982, Roy Moore has refused to drop out of the Alabama Senate race. None of these men face serious legal repercussions, despite the usually harsh sentencing against sexual crimes. It is a result of a legal system that “operates against offenders from deprived backgrounds and [over-represents them] in the criminal justice system” (Bagaric). The fact that these crimes are only becoming public knowledge now shows the protection from punishment that elites enjoy, and sexual crimes are a widespread and common form of elite deviance among the mostly white upper class.

1957–61: A federal jury convicted General Electric, Westinghouse, and 29 other manufacturers of heavy electrical equipment for price fixing and collusive bidding for the sale of electrical equipment valued at $1.74 billion per year. To date, this case is the largest price fixing case in the history of the Sherman Antitrust Act. This conviction of 45 multinational conglomerate executives marked the first instance the U.S. government jailed white collar criminals for their offenses. Nevertheless, the punishment for these companies was not substantial. GE received a fine of $437,000 – equivalent to a $3 parking ticket for a person who earns $175,000 per year.

1960s-70s: United States federal agencies, including the executive branch, Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) illegally tapped phones, and violated many civil liberties of those involved in the civil rights movement and anti-Vietnam war movement. Decades later, these agencies continue these actions. In 2013, Edward Snowden, a member of the National Security Agency’s (NSA) team of hackers, the Tailored Access Operations, leaked NSA files detailing the fact that that the NSA and its British counterpart, GCHQ, illegally tracked communications both online and offline. The agencies made use of an online surveillance program known as PRISM to tap directly into the servers of nine internet firms, including Facebook, Google, Microsoft and Yahoo. Additionally, the agencies made use of another program, DISHFIRE, to monitor the phone calls and messages of millions of citizens worldwide, including those of 35 world leaders.

1972: The Watergate scandal, a series of clandestine and often illegal activities undertaken by members of the Nixon administration, included “bugging” the offices of political opponents and people of whom Nixon or his officials were suspicious. Nixon and his close aides also ordered investigations of activist groups and political figures, using the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), and the Internal Revenue Service (IRS). The scandal began with the arrest of five men for breaking and entering into the DNC headquarters at the Watergate complex on Saturday, June 17, 1972. The FBI investigated and discovered a connection between cash found on the burglars and a slush fund used by the Committee for the Re-Election of the President (CRP), the official organization of Nixon’s campaign. The investigation also revealed that Nixon had a tape-recording system in his offices and that he had recorded many conversations. Forced to release the tapes by the Supreme court, the tapes revealed that Nixon had attempted to cover up activities that took place after the break-in, and to use federal officials to deflect the investigation.

1977–79: The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) conducted a sting operation in which agents pretended to be wealthy Arab sheikhs seeking investment opportunities in the United States. The FBI videotaped seven legislators, a senator, and six congressional representatives accepting bribes from undercover agents in return for political favors. The scandal became known as ABSCAM, after the bogus Abdul Enterprise Company set up by the FBI. This operation was later dramatized into many books and films, the most recent being 2013’s American Hustle.

1981: After the payment of $1.25 million to Carlos Velasquez Toro, the former operations manager of Puerto Rico’s Water Resources Assembly, a federal jury convicted three General Electric officials on charges of bribery (The New York Times 1981). The goal of their action was to secure a $92 million federal power plant contract for General Electric. More recently, Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority (PREPA) awarded a small Montana-based energy company (with only two employees) a $300 million contract to help rebuild Puerto Rico’s power grid after Hurricane Maria in September 2017 (Moore 2017).

1991: The U.S. Postal Service helped crack an art fraud ring marketing forgeries presented as paintings by master artists, such as Pablo Picasso and Salvador Dali. The Postal Inspection Service, along with the Department of Justice, the Federal Trade Commission, and Interpol conducted a sting operation that culminated in the discovery of over 100,000 pieces of bogus art (“Bogart”).

2008: Bernie Madoff’s Ponzi Scheme was a white-collar crime in which he stole an estimated $17.3 billion in lost principal investments from his clients, allowing him and his family to live lives of extreme luxury at the expense of unknowing investors. When the scheme collapsed, dozens of investors found themselves financially ruined. His scheme flourished for decades in part because of his close ties with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). Additionally, the public largely viewed Madoff as a titan of the investment industry due to his former status as president of the NASDAQ. These two characteristics, along with his philanthropic endeavors, enabled Madoff to maintain authenticity and a veil of secrecy to his client and the public, at large.

2010: The Deepwater Horizon disaster exposed a major failure of the federal agency empowered to regulate the oil drilling industry (Minerals Management Service). Regulators and employees of the companies they were meant to control repeatedly engaged in parties and interpersonal relationships with each other, often resulting in a lack of actual regulation. Employees of the regulatory agency often moved through a revolving door, at times working for the agency while at other times working for the oil companies. In the end, Secretary of the Interior, Ken Salazar, issued a secretarial order to break up MMS into several regulatory agencies with very narrowly defined roles and duties.

2015: The Panama Papers are 11.5 million leaked documents containing financial and attorney–client information for more than 214,488 entities. An anonymous source leaked the documents from a Panamanian law firm, Mossack Fonseca. These documents contained information about offshore shell corporations belonging to wealthy individuals and public officials. Typically, offshore business entities are legal; however, in this case, reporters from the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) found evidence of fraud, tax evasion, and evading international sanctions by Mossack Fonseca shell corporations.

Created by: Emily Jordan, Gus King, and Luo Yang

This article provides an example of elite deviance, focusing on Bernie Madoff — the perpetrator of one of the most well-known Ponzi schemes in America. In this article, the CNN Library provides a background on Madoff’s life, career and clients, and timeline of crimes.

Drugs Inc.: The Real Wolves of Wall Street

This video traces the producers, dealers, users, and law enforcement involved in the cocaine and drug world of white collar workers in New York City. More specifically, this National Geographic Drug Inc. episode depicts the widespread use of cocaine on Wall Street and the growing police prevention efforts.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=1&v=6cG9p4CjLIE

The Business of White Collar Crime

This video details the history of white collar crime, applications of Sutherland’s theory, and the societal factors that preserve the current system of elite deviance among the upper class. In particular, this video analyzes future impacts of recent corporate scandals, such as Enron, World Com, and Tyco.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MEoYxQgYT2w

Created by: Emily Jordan, Gus King, and Luo Yang

Simon, David. 1999. Elite Deviance.

Simon, David. 1999. Elite Deviance.

This book provides an in-depth analysis on elite deviance and its relationship to C. Wright Mills’ “power elite.” Simon includes descriptions on both corporate crime and political corruption, and provides historical and modern examples to contextualize the concepts.

Mills, C. Wright. 1956. The Power Elite. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Mills, C. Wright. 1956. The Power Elite. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

In The Power Elite, Mills examines the organization of power in America, and coins the term “power elite” to describe the military, corporate, and political elite — and the interdependent relationship of the three. Although this novel was written in 1956, its concepts and critiques are largely applicable in the contemporary context.

Friedrichs, David O. Trusted Criminals: White Collar Crime in Contemporary Society. Wadsworth, 2011.

Friedrichs, David O. Trusted Criminals: White Collar Crime in Contemporary Society. Wadsworth, 2011.

Friedrichs provides a careful, methodological study of white collar crime that includes the theoretical origins and current categorizations of elite deviance. This book considers a number of socioeconomic, racial and gender variables that contribute to the current state of widespread elite deviance.

Robinson, Matthew and Daniel Murphy. 2009. Greed is Good: Maximization and Elite Deviance in America. London, UK: Rowman and Littlefield Publishing.

Robinson, Matthew and Daniel Murphy. 2009. Greed is Good: Maximization and Elite Deviance in America. London, UK: Rowman and Littlefield Publishing.

Robinson and Murphy’s book offers new insights on the theory of elite deviance, and brings in a new theoretical framework (contextual anomie/strain theory) to explain the motivations of such deviance. This novel focuses on the legitimate and illegitimate means to pursue one’s financial goals within the corporate world.

Salinger, Lawrence M. 2013. Encyclopedia of White-collar & Corporate Crime. California, USA: SAGE Publications.

Salinger, Lawrence M. 2013. Encyclopedia of White-collar & Corporate Crime. California, USA: SAGE Publications.

The encyclopedia incorporates information about a variety of white-collar crimes and provides examples of persons, statutes, companies, and convictions. The authors of the articles are almost all current or retired academicians, and their articles serve as an introductory passage that readers can utilize for further research.

This article presents a holistic, intersectional approach to understanding white-collar crime. Additionally, through questionnaire interviews, the authors seek to understand the implications of the public’s lack of knowledge about white-collar crime.

Michael, Cochran, and Heide present information on the public understanding of white-collar crime, and the consequences of a lack of wide-spread knowledge. Specifically, the authors analyze the distribution of white-collar punitiveness across varying demographics.

In this article, Shapiro challenges the general conception of white-collar crime. Rather than focus on the role-specific norms of white-collar criminals, Shapiro exposes the strategies utilized by elite deviants to violate and exploit trust for personal gain.

Sutherland, E. 1945. “Is “White Collar Crime” Crime?” American Sociological Review, 10(2): 132-139.

This article is a formative piece for white-collar crime theory. In this article Sutherland establishes the concept of white-collar crime, and sets a precedent for understanding the evolution of elite deviance and white-collar crime.

Created by: Emily Jordan, Gus King, and Luo Yang