Body suspension is the practice of suspending an individual in the air using hooks pierced into their skin or hooks attached to already existing piercings (Forsyth and Simpson 2008:367). Today, body suspension is a practice typically attributed to individuals who are heavily involved in body modifications such as tattoos or piercings, yet it has a history of being practiced by various cultures for thousands of years. The historic origins of body suspension are discussed later in this page, and this section will focus on the modern era of this subculture.

Broadly, there are two different contexts in which body suspension can occour: public or private. Public suspension are typically performed at clubs, concerts, or festivals and are meant to be a spectacle that is viewed by an audience (Federica. 2023:4). In this context, suspension is meant to draw attention to the performer and can operate as a “wow factor” that helps cement the memory of the performance in the audience’s memory. An example of this is when artist Miguel inserted hooks into his back and hung over stage during one of his concert performances in August of 2023 (Powel. 2023). Private suspensions, conversely, place less emphasis on the performance aspect of body suspension and instead place a focus on the experience of the individual who is hanging. People may choose to privately suspend for a variety of reasons including, but not limited to, exploring the unknown, expanding their consciousness, getting an adrenaline “rush”, or testing their physical limit (Forsyth and Simpson. 2008:370). Individuals who suspend report that the experience can be therapeutic in many ways and help in healing trauma their dealing with. Although the reason for why someone suspends can be complex and multifaceted, people who perform body suspension can be mislabeled as masochistic or sadistic. This perception of body suspension, however, fails to capture the deeper motivations for why people suspend and unintentionally subverts the historic relevance this practice has for several cultures around the globe.

Pain is an almost inherent part of body suspension, as suspending from hooks places an immense amount of strain on the pierced areas of skin. Pain, however, is not the primary reason most individuals are attracted to this subculture. People who suspend report that the pain subsides after some time as the skin becomes acclimated to the stress caused by the piercings. The euphoric and liberating effects of body suspension become more prevalent after this initial pain has dissipated (DeBoer et al. 2008:4). Although body suspension can be painful at times, trained professionals take great care to ensure the safety of individuals who chose to suspend. Sterile equipment and mindful placement of hooks are some of the precautions taken by these professionals to minimize risk of infections or accidents during suspension (DeBoer et al. 2008:2).

Body suspension has existed in various cultures for hundreds of years and here we describe two examples of this practice used within Native American rituals. The first example is the Sun Dance ceremony performed by the Lakota Sioux, a tribe of Native Americans that currently reside in North and South Dakota (Hämäläinen. 2009:384). Prior to the ceremony, a cottonwood tree is erected in the center of a circular dance ground and numerous ropes are tied to it (one for each dancer). Bags of tobacco and buffalo hide paintings depicting men hunting are also tied to the tree as a sacrifice to the spirits. The most intense part of the ceremony happens when male members of the tribe have two cuts made on each side of their chest to allow wooden pegs to be inserted beneath their pectoral muscles. These pegs are then tied to the ropes which have been fastened to the tree and the dancing begins. The dancers oscillate between the base of the tree and the edge of the dance circle three times, pausing each time to pray at the base of the tree. Then, as the dancers near the periphery of the dance circle a fourth time they break into a run and hurl themselves backwards, causing the wooden pegs to rip through their skin (Lincoln. 1994:7). The breaking of the skin serves as a rite of passage within this tribe, and one interpretation of this ceremony is that overcoming the pain caused by tearing the piercing signals to others that the dancer is a respectable warrior (Mails. 1998:37). Importantly, being seen is an inherent part of this ceremony as tearing the pegs through the skin happens at the center of the dance circle. The communal identity established within the Sun Dance ceremony parallels the spectatorship seen during a modern public body suspension. A connection is made between the performer and the audience that is never explicitly verbalized yet remains equally tangible.

A similiar ritual was performed by the Mandan tribe during their O-kee-pa ceremonies. Here, young male members of the tribe were first instructed to complete a three day fast in which they were not allowed any meat or drink. They were then stripped of their clothes and brought to the foot of a 15 foot tall post that had ropes secured to the top. An elderly member of the tribe cuts incisions in the chest of the younger tribe member and inserts two wooden skewers on either side of their chest. These skewers were fastened to the ropes and the tribe member was hosted up so that their feet floated above the ground, causing the skin of their chest to stretch several inches. Exhausted and starved, the tribe member was to stay suspended in the air until their skin broke and they were set free of the post. This process was neither passive nor serene, as members of the tribe would swing and twist while yelling prayers to the Great Spirit that this ritual would help them to become successful warriors whose hearts were strong enough to bear the present suffering (Saunders and Zuyderhoudt. 2004:203).

The practice of body suspension borrows largely from ritualistic practices that date back hundreds of years. Currently, body suspension is practiced globally and a considerable amount of literature has studied this subculture in both North American and European context. As the subculture continues to grow it is important to remain cognizant of its origins and the many nuanced reasons that an individual may choose to suspend. For some it is a cultural rite of passage, yet for others it is the therapeutic act of expanding consciousness and exploring the unknown.

Identity within the subculture of body suspension operates at several different levels. Firstly, there is there is the baseline communal identity formed between people who perform and/or enjoy body suspension. People within this subculture no longer view the practice through deviant labels placed onto it by mainstream society. To them suspending is not something revolting or masochistic, rather it is a common interest that can be used to foster connection between two strangers. Secondly, there is the connection made between the person being suspended and the professional suspending them. An individual who wants to suspend needs to place an immense amount of trust in whoever is rigging them up, and this lending of trust I argue creates an entirely new layer of identity building. The last layer of identity occours specifically in public suspensions and is made between the person being suspended and the audience. These levels of identity formation mirror the communal identity experienced in other body modification artforms such as tattoos or body piercings.

Body suspension actively resists mainstream ideas of how the body can be used and notions surrounding pain. By willingly subjecting oneself to the intense physical sensations of piercing and suspension, practitioners defy conventional notions of comfort and safety, asserting autonomy over their bodies and experiences. Moreover, body suspension can also be a form of resistance against the constraints of conventional spirituality and religious dogma. Many practitioners approach suspension as a deeply personal and spiritual journey, using the experience to explore existential questions, transcend physical limitations, and connect with the divine on their own terms. In this way, body suspension serves as a rejection of prescribed religious narratives and an assertion of individual agency in matters of faith and spirituality.

Short YouTube documentary on body suspension giving further visual and auditory insights into the subculture of body suspension. The documentary includes interactions with individuals who perform body suspension.

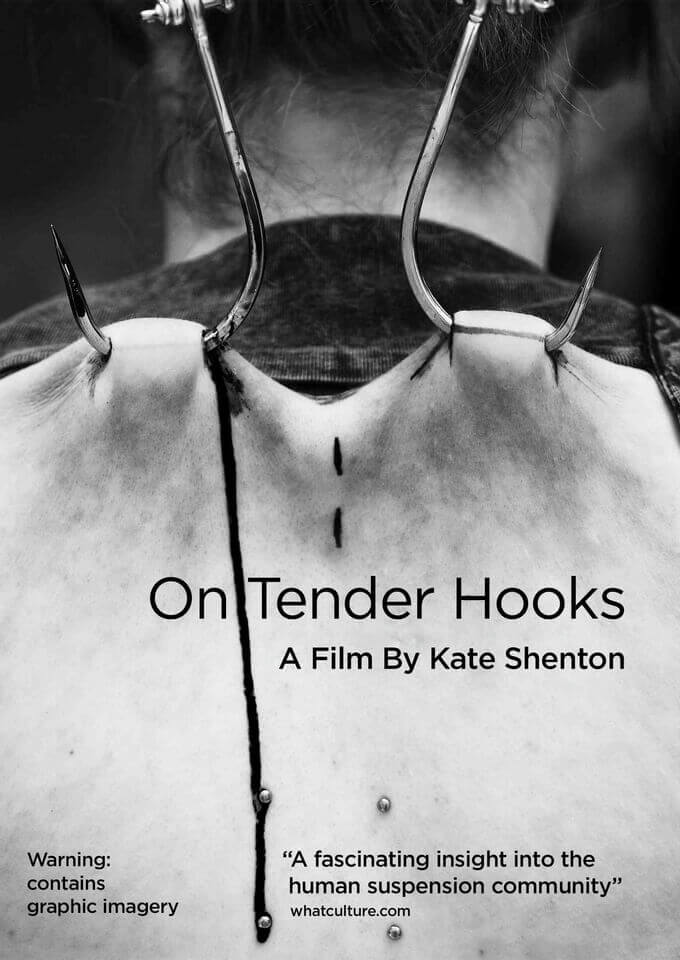

Shenton, Kate. 2013. On Tender Hooks. United Kingdom. Independent Film.

Independent documentary focused on the subculture of body suspension.

Paramount. 1970. A man called horse. United States.

A film about a cowboy named Horse whose experience during a body suspension ceremony leads him to joining a Native American tribe.

Flying high by Heidi Saevareid

Heidi Saevareid is a Norwegian author and literary critic who wrote a blog detailing her experience with body suspension. She dives into mainstream conceptions about pain and how this can influence an individuals choice to suspend.

Body Suspension by Lynn Loheide

Lynn Loheide is an internet personality who makes content centered on body modification. In this blog post she answers common questions about body suspension and inserts personal anecdotes.

DeBoer, Scott., Allen Falkner and Troy Amundson. 2008. “Just Hanging Around: Questions and Answers About Body Suspensions.” Journal of Emergency Nursing: 1-7.

Federica Manfredi. 2023. “Thinking the Self through Hooks, Needles, and Scalpels: Body Suspensions, Tattoos, and other Body Modifications.” Medicine Anthropology Theory 10(3):1-25.

Forsyth, Craig and Jessica Simpson. 2008. “Everything Changes Once you Hang: Flesh Hook Suspension.” Deviant Behavior 29: 367-387.

Hämäläinen, P. 2019. “Epilogue: The Lakota Struggle for Indigenous Sovereignty.” Yale University Press 1:380-392. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvqc6gp2.15

Lincoln, Bruce. 1994. “A Lakota Sun Dance and the Problematics of Sociocosmic Reunion.” History of Religions 34:1–14.

Rada, Julia. 2014. Extremely Up-in-the-Air: Flesh Hook Suspension and Performance. Oxfordshire, United Kingdom: Inter-Disciplinary Press

Mails, Thomas E. 1998. Sundancing: The Great Sioux Piercing Ceremony. Oklahoma, United States of America: Council Oak Books

Saunders, Barbra and Zuyderhoudt, Lea. 2004. “George Carlin’s Account(s) of the O-kee-pa in Concordance with Other Sources.” Pp. 185-207 in The Challenges of Native American Studies. Leuven; Leuven University Press.

Powel, Jon. 2023. “Miguel shares gruesome photos after back suspension performance.” Revolt. Retrieved February 25, 2024 (https://www.revolt.tv/article/2023-08-29/324335/miguel-shares-gruesome-photos-after-back-suspension-performance).

Stefanoff, David. Spring 2024. [date accessed]. “Body Suspension” in Subcultures and Sociology.